(This article was partially reproduced with full permission via Creative Commons from Offbeat Oregon. We love their site...give them a browse sometime.)

If the idea of cable car service to Mt. Hood's historic Timberline Lodge strikes you as a not particularly bad one, you’re not alone. The lodge gained a place in movie history for being the filming location of the exterior shots of the Grand Overlook Hotel in 1980s The Shining. Who wouldn't want a quick and scenic way to get there?

The Mt. Hood Skiway Trolley

The Skiway (originally “Skyway,” but that name turned out to already be trademarked) was the brainchild of Dr. J. Otto George, who came up with the idea just after the Second World War, as the popularity of skiing started to explode nationwide. With a group of other investors, he formed the Mount Hood Aerial Transportation Co. to implement his plan. The route would tote passengers from a lower terminal in Government Camp (now Thunderhead Lodge) up the side of the mountain to Timberline and back again.

Image via / OHS Research Library, Org. Lot 1027, Oregon Journal photographs collection, photographer Ray Atkeson

The idea would be, rather than properly engineering a six or eight-passenger gondola in the usual way, to incorporate the latest skyline-logging technology to hoist an entire city bus into the air and haul it up the side of the mountain. Each bus (there were two of them) was modified somewhat crudely to transfer the power from the drive wheels up to a 1.5-inch overhead traction cable, along which it would claw its way up and down the mountain.

The whole project would use off-the-shelf parts and equipment modified to work in this new context, so it would be relatively cheap from a research-and-development standpoint. Per the Oregon Historical Society:

Outfitted in Portland by Willamette-Pointer, the buses each used two 185-horsepower gasoline engines to haul the bus up a stationary 1.5-inch diameter cable — a technology also used in timber operations to haul logs out of the woods.

-OHS

Well, that seems safe.

Most truly bad ideas are good ideas gone awry through some key detail being overlooked or superadded. Not this one. The Skiway was a bad idea through and through, from the very start. It was slow, loud, and expensive. Enormous amounts of force had to be applied to the traction cable just to move it up the side of the mountain, so the trolleys required two regular bus engines, one at each end, running flat out. The engines weren’t diesel ones, so they could have been louder; but nonetheless, they were plenty noisy, too loud for passengers to carry on a conversation during the trip.

Image via / Vintage Everyday / Original author unknown.

It was also terrifying. A city bus full of passengers weighs 15 to 20 tons, which is a lot of weight to have dangling from a cable in the air. The weight dragging down the cable would make it sag deeply as the bus moved from one piling to the next. The trip up the mountain became a roller-coaster-like cycle of the tram clawing its way up to one of the towers and then almost free-falling down the other side (nose down, of course) before starting the climb to the next. It was not for the faint of heart, nor for the afraid-of-heights.

Skiers wait on the loading platform at Timberline Lodge / Image via / portlandhistory.net

“I’ve ridden the tramway,” board member George Rauch said, at one of the later company meetings, as the failure of the venture was becoming obvious. “I’ve listened to the shrieks and I’ve taken the jolts over those, what you call them — the saddles, and I’ve heard what people say.”

All of these issues might have been okay, but at just about the same time the Mt. Hood Skiway opened for passengers, improvements to the highway to Timberline eliminated one of its primary reasons for being. One could now drive to Timberline, or take a ground-based shuttle bus, and get there ten minutes quicker (and, in the case of the bus, for 25 cents less; the tram was 75 cents one-way, and the buses were 50).

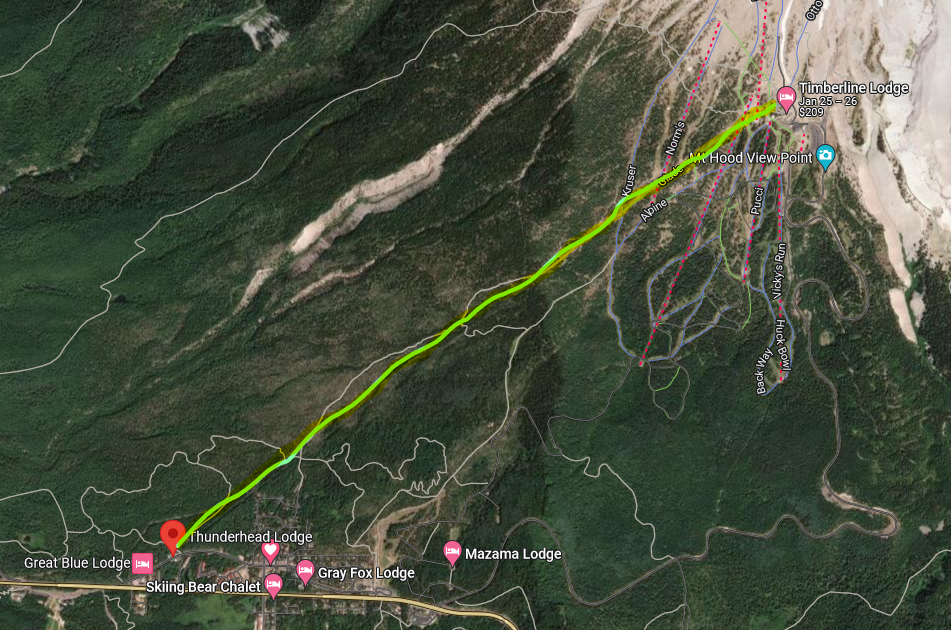

My very poorly rendered map of the original route taken by the Skiway.

When the Skiway flying-bus service opened in 1951, there was considerable nationwide fanfare, and lots of people lined up to ride it. But for most of them, once was enough. Activity quickly dropped off to the point where the sky-buses were idle for months on end. By 1956, the run was shut down, and the Mount Hood Aerial Transportation Co. board was faced with some hard decisions.

Notice how not a single passenger disembarking the tram in this 1956 newsreel has a smile on their face.

Should they pull the buses and replace them with smaller cars? What about investing in a ground-traction system, like ski lifts use, to reduce the weight and noise?

But all these options cost money, and the board had no stomach for risking further sums. A liquidation committee was formed, and by the early 1960s, the sky-bus line was no more.

Despite these discussions, further attempts were made to save the Mt. Hood Skiway tram throughout the remainder of 1958 and into the next year. By June of 1959, despite repeated efforts to carry out experiments for a redesign, a Liquidating Committee was formed. Over a year later, the lower terminal building was sold in 1960 to stockholder William Simon, for $25,000. In December of 1960, Zidell Machinery & Supply Company bought the two buses, a jeep, an engine, and other tram parts for $10,080.

-OHS

Today, the lower Mt. Hood Skiway terminal still exists (albeit remodeled) as the Thunderhead Lodge.

Thunderhead Lodge today was once the lower terminus of the Skiway. / Image via / motels.com

In spirit, the failed tram line lives on in the naming of the Skyway Bar and Grill, an excellent BBQ restaurant in Zig Zag, just a few miles west of Government Camp.