November is National Native American Heritage Month in the United States, the perfect occasion to celebrate rich and diverse cultures, traditions, and histories and to acknowledge the important contributions of Native tribes and our Northwest Native Americans. Heritage Month is also an opportune time to educate the general public about tribes, to raise general awareness about the unique challenges Native people have faced both historically and in the present, and the ways in which tribal citizens have worked to conquer these challenges.

Northwest Native American Tribes

Today, Oregon officially recognizes nine Confederated Tribes, and the State of Washington 34 Tribes and Nations. We have chosen only ten of so many Northwest Indigenous Peoples to highlight in this article, but we encourage everyone to continue reading beyond the stories of these courageous individuals.

1. Billy Chinook (c. 1827-1890)

Wasco Tribe, Oregon

Tsagaglalal, or "She Who Watches". Wasco-Wishram Tribal Petroglyph. / Image via / Kael Godwin / Wikipedia

When you search the internet for "Billy Chinook", most results consist of the Central Oregon lake named after him by the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs. However, there is an important man behind the name.

Billy Chinook (William Parker) was born around 1827 in the area that would become The Dalles, Oregon. Billy was an orphan raised and baptized Methodist by the Reverend Jason Lee of the Wascopam Mission. In 1843 when he was about 17-years-old, Billy was recruited as a guide by famed white explorers Kit Carson and John C. Frémont who were on an expedition through Central Oregon territory. Over the following years, he traveled around the US with Frémont and attended college at Columbian University in Washington D.C.

By the time Billy returned to Oregon with his Californian/Mexican wife he was ready to use his time spent with white folks to his advantage.

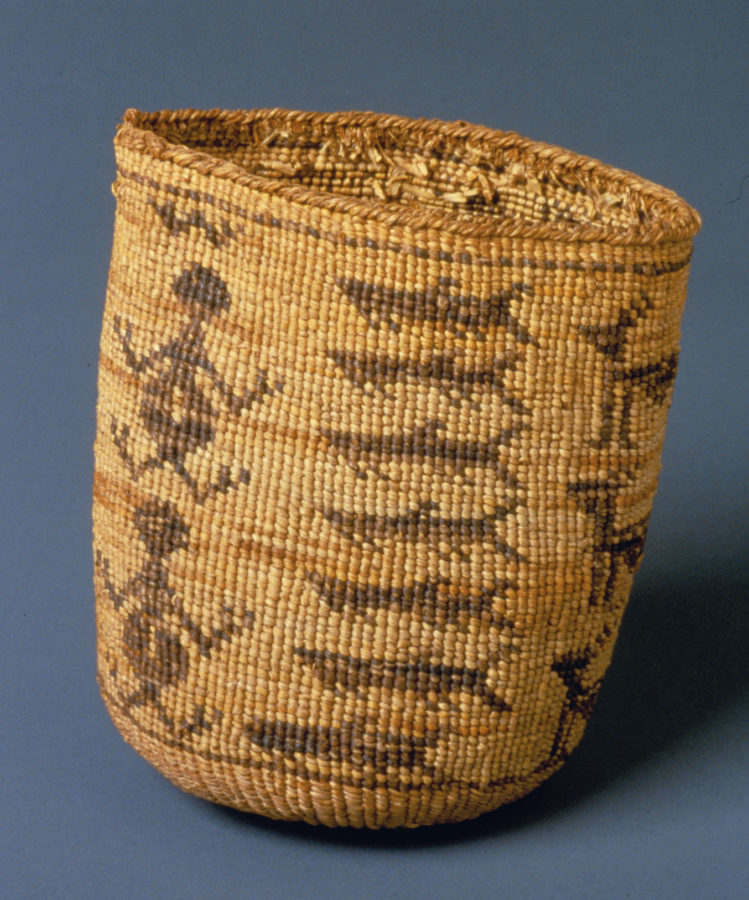

Wasco Twined Bag Showing Frog and Sturgeon Motifs, 19th century. / Image via / Maryhill Museum of Art

Billy settled with his wife on a land claim at his native village near The Dalles, Oregon in 1851 and set to work. Using his excellent English skills he was able to become an invaluable assistant to his people.

In 1853 Billy wrote a letter to Joel Palmer, Oregon Superintendent of Indian Affairs asking him to protect native lands at The Dalles area from encroachment by non-native settlers. In 1855 he represented the Wasco Nation at treaty negotiations with the U.S. government. Billy was also a signatory to the treaty that eventually established the Warm Springs Reservation. He continued to champion the cause of the Wasco Nation until his death on December 9, 1890.

Billy is buried in the Warm Springs Agency Cemetery.

2. Esther Ross (1904-1988)

Stillaguamish Tribe, Snohomish County, Washington

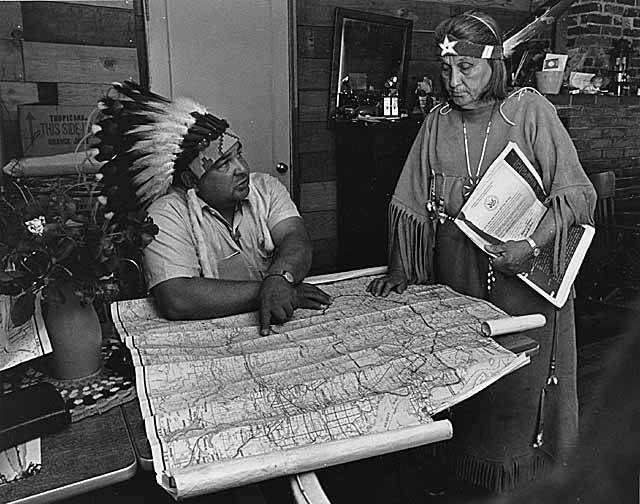

Frank Allen and Esther Ross looking at a map to plan tribal fish-in, 1968. / Image via / washington.edu / Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, Museum of History & Industry, Seattle; All Rights Reserved

In 1855, the United States signed the Point Elliott Treaty with a number of Native American tribes in what is now Snohomish County in Washington State. At the mercy of the US Army, tribal leaders could do little more than sit back and watch as their people were surrendered to small reservation lands. The Stillaguamish ("People of the River") was tiny in comparison to larger tribes in the area. Their chief didn't understand in signing the Point Elliott Treaty that the United States had not even considered his people worthy of a reservation of their own. They would not be alive today if not for Esther Ross.

Born in 1904, Esther took great pride in the stories of her tribe passed down from her great-grandfather, Chief Chaddus, but white friends shunned her heritage. This was her first taste of social injustice and it changed the course of her life.

Ester was tireless in her lifelong campaign for recognition of her Stillaguamish tribe. She won small legal victories over the United States government over the years, but it wasn't until standing up to a 1976 Oregon Trail Bicentennial wagon train that her efforts started to be rewarded.

The 1976 Bicentennial Wagon Train stopped by Esther Ross, 1975. / Image via / pennlive.com

As the wagon train approached Stillaguamish land on June 8, 1975, the federal government had still not legally recognized her tribe. Esther was 72-years-old at this point and still not backing down. She approached the ceremonial wagon train in front of hordes of reporters, seized the lead horse's reins, welcomed the white men, and spoke: “We stop this Bicentennial wagon train, to bring to the attention of the nation that we have no other alternative, short of violence, to bring their plight to light and produce action.” She then handed the wagon master a letter addressed to the Secretary of the Interior and bid them farewell.

In October of the same year, the federal government finally gave Esther and her Stillaguamish people the respect they had been denied for over 100 years. The United States recognized the tribe, and her people bestowed her the rank of Chief.

Read more of Esther Ross' story here.

3. Chief Don Ivy (1951-2021)

Coquille Tribe, Oregon

Don Ivy / Image via / OPB / the Coquille Indian Tribe

Don Ivy was an award-winning leader, educator, and tribal scholar, beloved by all who met him. While heading the Coquille Tribe’s cultural program, he oversaw the creation of the Kilkich Youth Corps, which provides workplace skills, mentoring, and summer employment to tribal teens. Don's lifetime endeavor was to work in growing knowledge, understanding history, and engaging youth.

When he passed away in July 2021, a nation mourned.

“Chief Ivy was a consistent source of wisdom and kindness for the Coquille people. His voice was an invaluable asset to those of us who were privileged to serve with him in tribal leadership, and we will miss him terribly. We offer our prayers for his family, along with our enduring gratitude for his many contributions to the tribe’s wellbeing.” --Coquille Tribal Chairman Brenda Meade

Ivy had served as chief of the Coquille since 2014. In 2013 the state of Oregon honored him with its Heritage Excellence Award. The following year, the University of Oregon appointed Ivy as its first-ever Tribal Elder in Residence.

He went on to be honored as a 2021 Distinguished Alumnus by Southwestern Oregon Community College just before his passing. Under his leadership, the Coquille Indian Tribe was the college’s first vocal supporter and partner in building the college’s new Health & Science Technology Center. The building will open in fall 2021, providing modern labs for training new generations of scientists, engineers, and health care professionals. --SOCC.edu

That Oregon Life interviewed Don in 2018. Watch here:

4. "Kennewick Man"

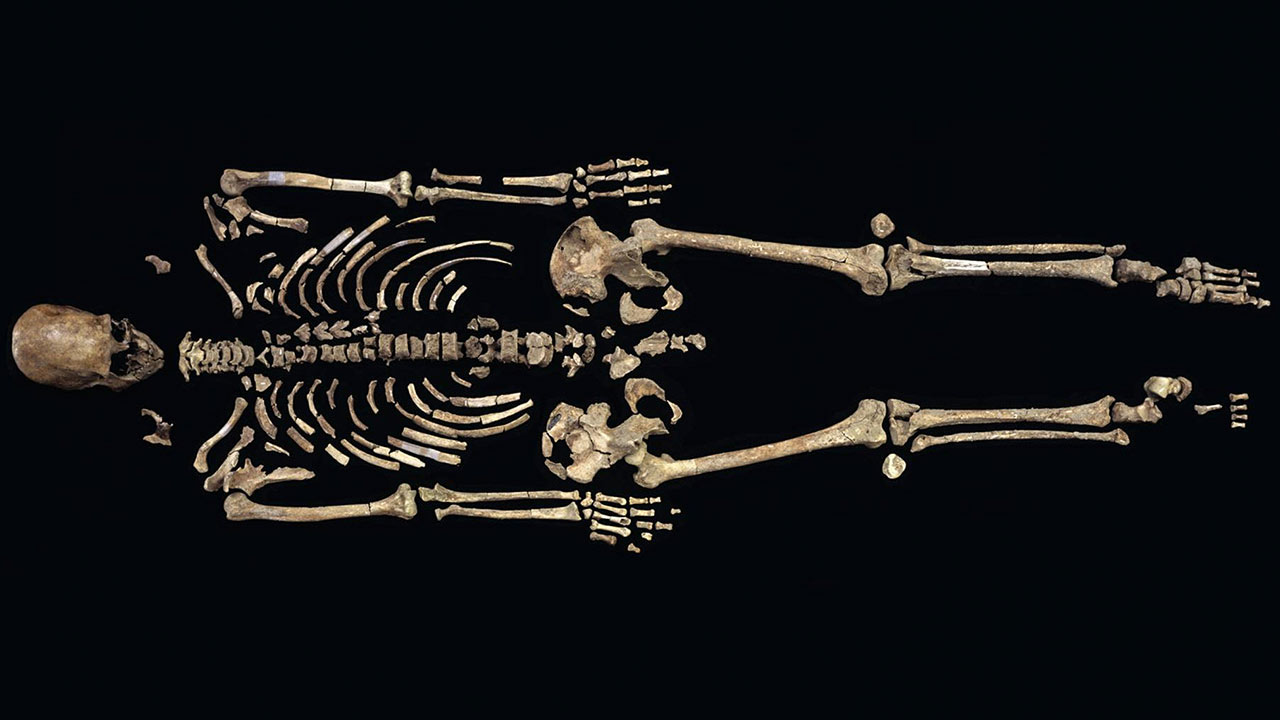

Kennewick Man. / Image via / Chip Clark / Smithsonian Institution / science.org

Although Kennewick Man has no name or tribe, he has been posthumously instrumental in Northwest Indigenous History. To Native tribes, he is the "Ancient One".

Back in July 1996, Will Thomas and David Deacy were just spectators at the annual hydroplane races near Kennewick, Washington. They decided to take a wade in the shallows of the Columbia River when one of them accidentally stepped on a rock...a rock with teeth that turned out to be a human skull.

The coroner was called in. After eliminating the possibility of a crime scene AND the likelihood that the skull belonged to an early white settler in the area, forensic analysis solved the mystery. They dug the rest of the skeleton out of the mud and eventually concluded that Kennewick Man was between 9,200 and 9,600 years old. His was the oldest near-complete skeleton ever found in North America up until that time.

The discovery of Kennewick Man, along with other ancient skeletons, has furthered scientific debate over the exact origin and history of early Native American people. His genome makes him a prehistoric Paleoamerican. One of the first peoples to enter and inhabit the North American continent.

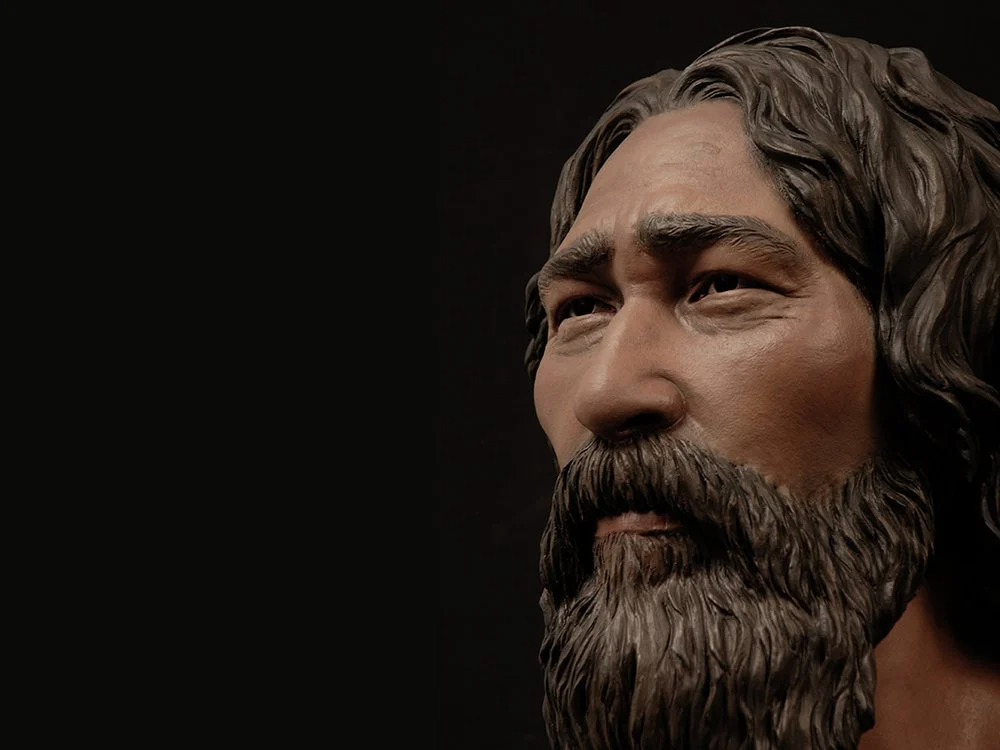

A facial reconstruction of Kennewick Man / Image via / StudioEIS / smithsonianmag.com

In September 2016, the US House and Senate passed legislation to return the ancient bones to a coalition of Columbia Basin tribes for reburial according to their traditions. The Ancient One's remains were buried on February 18, 2017, with 200 members of five Columbia Basin tribes in attendance, at an undisclosed location in the area.

5. Marie Dorion, Marie L'Ayvoise (1786–1850)

Ioway Bah-Kho-Je Tribe, Oklahoma, Settled in Oregon

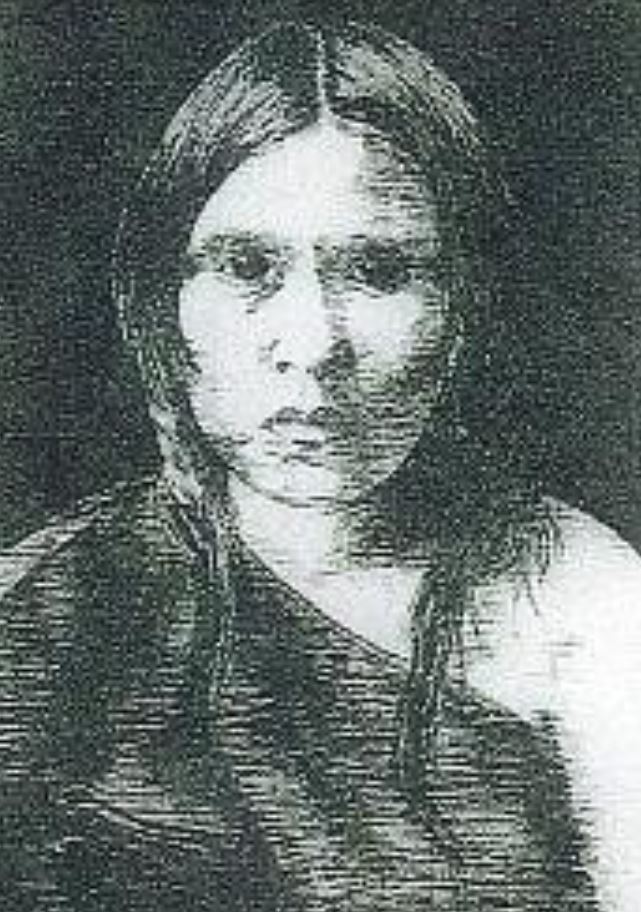

Artist's Depiction of Madame Marie Dorion.

Marie Dorion was born to the Ioway Tribe near St. Louis, Missouri but she's best known for her incredible journey to Oregon. In fact, she was the first pioneer woman to cross the continent overland and settle in the Oregon Country.

She was a young wife to Pierre Dorion when he told her they were going west with John Jacob Astor's Pacific Fur Company. Marie was 21, pregnant, and not in a hurry to leave so her husband beat her.

What followed is a story to rival any wilderness survival epic out there, which you can read in greater detail here.

Marie traveled over 3000 miles on foot with her husband and two little boys. She gave birth alone on the trail to a baby who died but six days later. After reaching Astoria they set off again back toward Idaho, only for Marie to witness the slaughtering of Pierre and all the men by a rival native tribe. Alone and scared, she fled with her boys to Oregon's Blue Mountains in the middle of winter. There in the deep snow, she sheltered her family, subsisting off of mice and the horse that she butchered.

“When they could go no further, the children’s feet bleeding, Marie burrowed a hole in the snow, lined it with furs, stashed Paul and Baptiste inside, and went for help. She was wandering partially snow-blind when rescued by the Walla Walla tribe and taken to their village. Braves were immediately sent for her sons.”

Marie Dorion memorial near St. Louis Catholic Church, St. Loius, Oregon. / Image via Andrew Parodi / Wikicommons

Marie eventually married again and settled in what is now St. Louis, Oregon. She has been called the "Madonna of the Trail", "Walks Far Woman", and "Madame Dorion" out of deep respect for her journey and accomplishments. When she passed away in 1850 she was buried in a place of honor beneath the altar of the little church in St. Louis. A monument was erected in remembrance of this stunning woman.

6. Chief Seattle, Si'ahl (1786-1866)

Duwamish and Suquamish tribes of the Salish Peoples, Puget Sound, Washington

The only known photograph to exist of Chief Seattle, 1864.

Called Sealth by his native Suquamish tribe, Hudsons Bay Company traders gave him the nickname Le Gros, "The Big Guy". And he was. Broad-shouldered and standing around 6 ft tall, Seattle had an imposing presence that made people take notice.

As a six-year-old boy, Seattle witnessed British Captain George Vancouver's ships passing through Puget Sound in 1792. Later he also saw the devastation of disease brought by the white man to his native lands. As a young warrior, Seattle was known for his courage, daring, and leadership in battle against rival tribes in the area.

He inherited the position of Chief or Tyee from his mother's lineage, and by 1851, Chief Seattle was a strong leader respected for his peaceful ways, not his prowess at war. When the first wave of European settlers arrived in Puget Sound, he welcomed them, and immigrants saw him as an intelligent man striving to live amicably and peacefully with the newcomers.

Under Seattle's leadership, the Duwamish tribe helped their white neighbors immensely. They cleared land for new crops, provided seed potatoes, and cut down trees for canoes and housing, sharing their skills and knowledge with the immigrants.

The 1912 monument to Chief Seattle, Seattle, Washington, 2012. / Image via / Flickr / Clappstar

Despite this, the 1850s were a dark time for the Salish peoples. Whites were making an influx to the Puget Sound area at an alarming rate, greedily claiming more land and causing discontent. Violence erupted, and Washington Territorial Governor Issac Stevens was only out to aid the European settlers and himself. Stevens began buying up or seizing Salish lands and removing the tribes to reservations. In 1854, Chief Seattle gave his famous speech, saddened that the day of his peoples had passed and the future belonged to the white man.

According to historynet: Three years later, an old and impoverished Tyee Sealth spoke one last time for the record, wondering why the treaty had not been signed by the Congress of the United States, leaving the Natives to languish in poverty. His words are heartbreaking.

"I have been very poor and hungry all winter and am very sick now. In a little while I will die. When I do, my people will be very poor; they will have no property, no chief and no one to talk for them."

The resting place of Chief Seattle. / Image via / Jana Hawes Robertson / findagrave.com

Chief Seattle is buried at the Suquamish Tribal Cemetery on Washington’s Kitsap Peninsula.

7. Old Chief Joseph, Tiwi-teqis (c. 1785-1871)

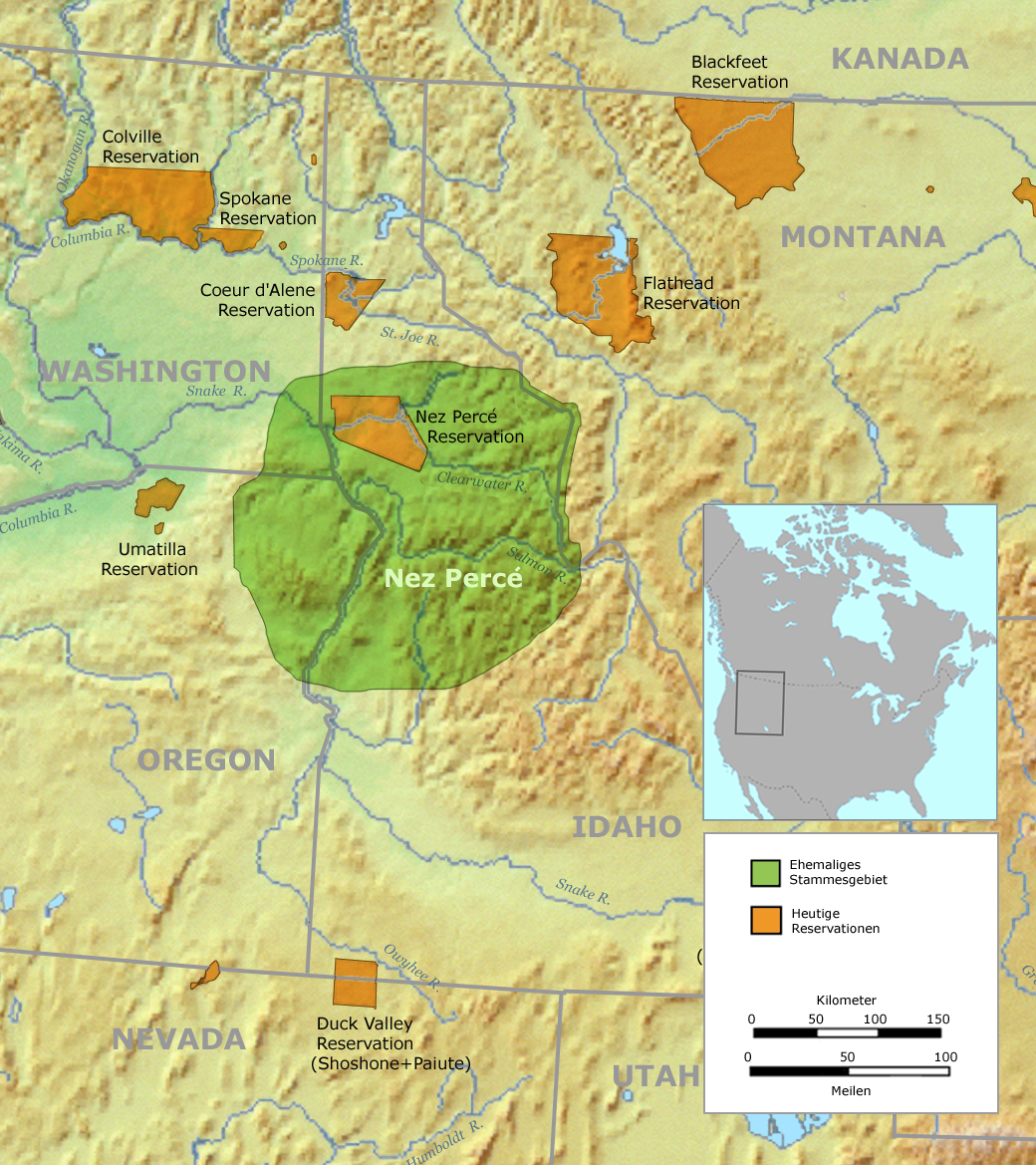

Wallowa Band of the Nez Percé Tribe, Oregon and Idaho

Detail from the grave of Old Chief Joseph, Joseph, Oregon. / Image via / The Oregonian / Jamie Francis

Echoing the legacy of Chief Seattle, his contemporary Chief Joseph the Elder faced similar circumstances in the persecution of his Nez Percé tribe. Like Seattle, he was an early convert to Christianity and attempted to be a peacemaker between his people and the white man.

In 1855, in a spirit of coexistence Old Joseph signed a treaty with the U.S. government. In it, the Nez Percé agreed to give up a portion of their ancestral lands in return for a guarantee from the Governor that whites would not encroach upon their sacred Wallowa Valley. They were promised financial rewards, schools, and a hospital for the reservation.

By 1863, that promise was shattered by greed and gold. As prospectors and settlers rushed into the northeastern Oregon Wallowas, old treaties were forgotten. The U.S. government offered up a new one that would remove Nez Percé control of the valley and confine the entire tribal nation to a 10,000-acre reservation in Idaho.

In 2017 I paid my respects to Old Chief Joseph at his gravesite near the town that is now his namesake. / Image via / The Author / thePDXphotographer

Old Joseph would not comply. It is said that he slashed his American flag, shredded his Bible, and refused to sign the new treaty or move his people. On his deathbed in 1871, Old Chief Joseph's standoff with the U.S. government became his son's battle to wage.

Young Chief Joseph would always carry with him his father's last words: "This country holds your father's body. Never sell the bones of your father and your mother."

Visit his gravesite near the city of Joseph, Oregon.

8. Young Chief Joseph, Hinmuuttu-yalatlat (1840-1904)

Wallowa Band of the Nez Percé Tribe, Oregon and Idaho

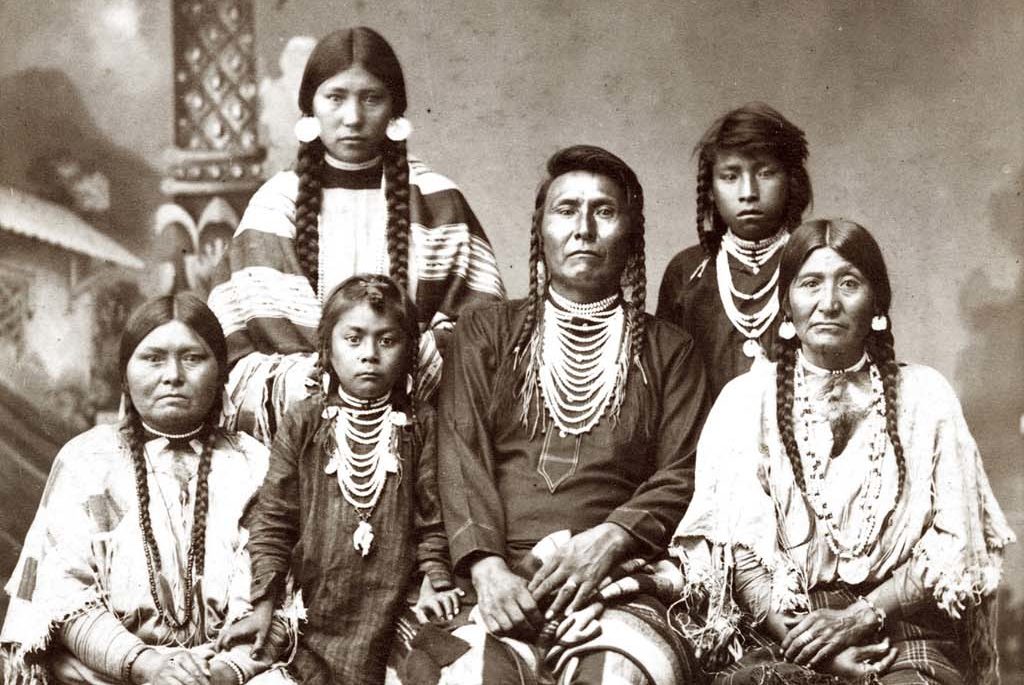

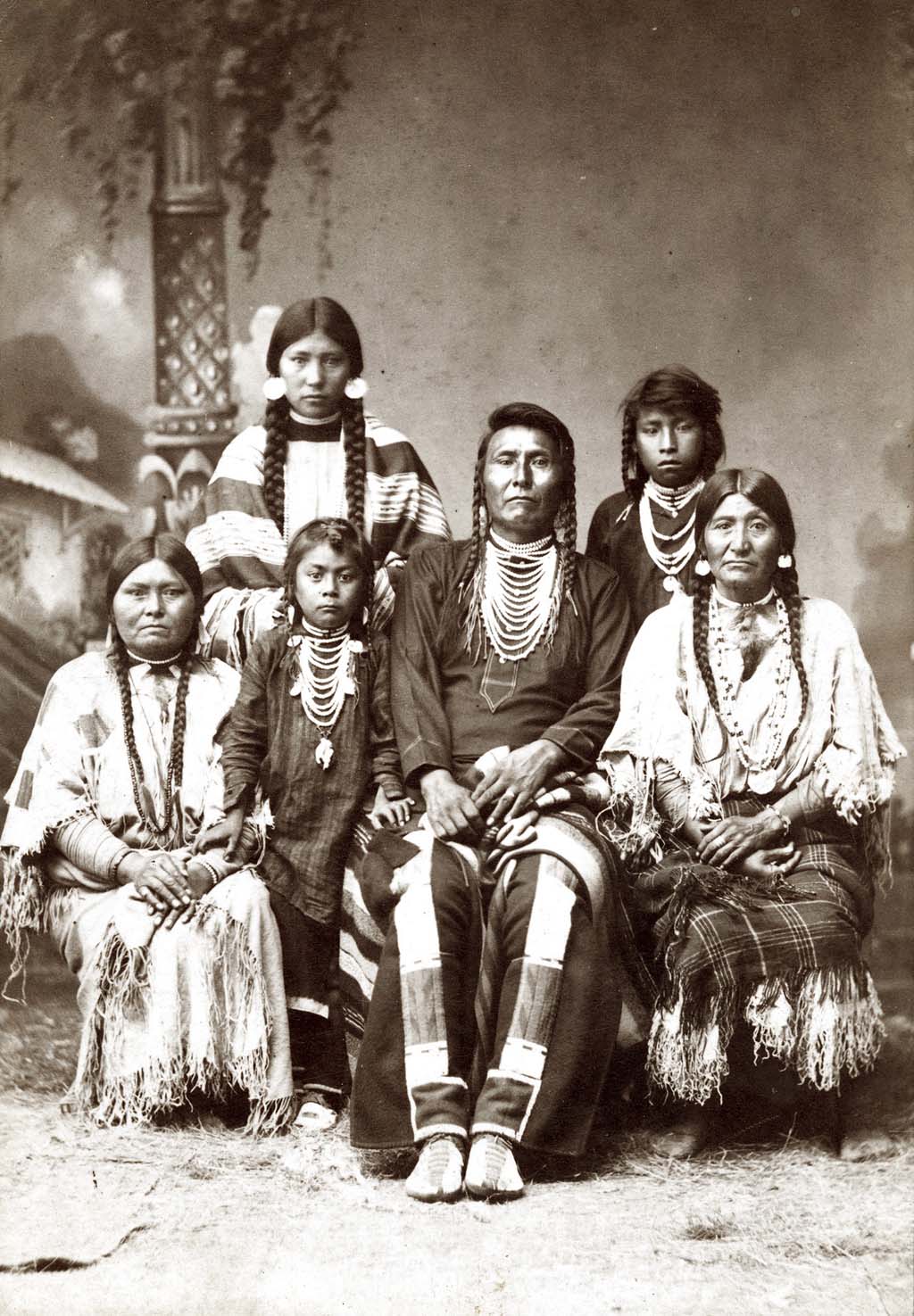

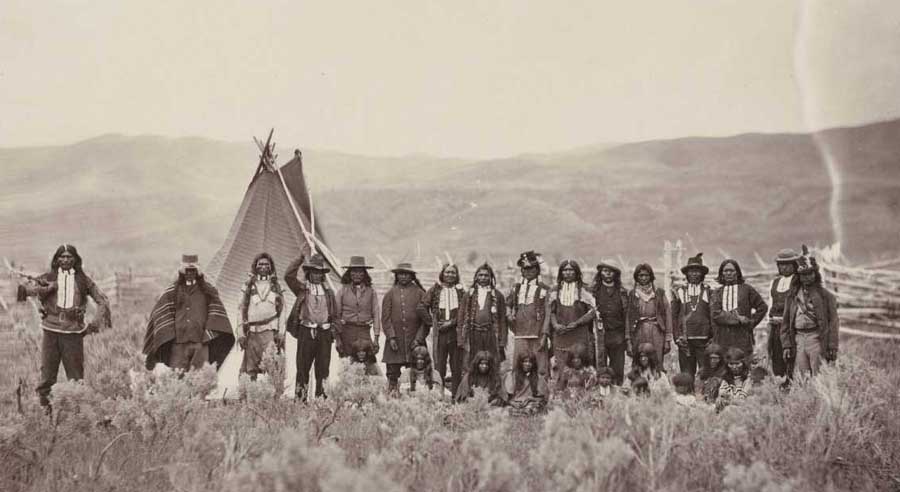

Young Chief Joseph of the Nez Percé and his family, 1880. / Image via Washington State Historical Society

His name means "Thunder Coming Up Over the Land From the Water".

When Old Chief Joseph died, his son related, "I clasped my father's hand and promised to do as he asked. A man who would not defend his father's grave is worse than a wild beast."

Now Chief in his own right, Young Joseph took up his father's legacy despite constant lies and reneging from the US Government. In 1873, Young Joseph negotiated with the federal government to ensure his people could stay on their land in the Wallowa Valley, but by 1877 they had reversed their policy yet again. Unable to find any suitable land on the proffered Idaho reservation that wasn't inhabited by the white man, he made one last effort to stay in the Wallowa Valley, but this fell on deaf ears.

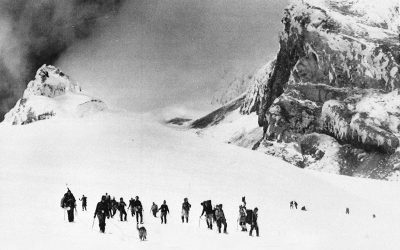

Young Chief Joseph was informed that his people had 30 days to collect their livestock and move to the reservation. He pleaded for more time but was told that any Nez Percé presence in the Wallowa Valley beyond the 30-day mark would be considered an act of war, and war they did.

Image via / Wikipedia

The U.S. Army's pursuit of about 750 Nez Percé and a small allied band of the Palouse tribe, led by Chief Joseph and others, as they attempted to escape from Idaho became known as the Nez Percé War. Following a devastating five-day siege during freezing weather, with no food or blankets and the major war leaders dead, Chief Joseph formally surrendered to General Miles on the afternoon of October 5, 1877. 150 of his followers had been killed or wounded.

Young Joseph and 400 of his people were taken by train cross-country to Oklahoma. During the seven years they were kept there as "prisoners of war", many died of epidemic diseases to which they had little immunity.

It wasn't until 1885 that Young Chief Joseph and his followers were granted permission to return to the Pacific Northwest, but not to their ancestral homeland. They were taken to the Colville Indian Reservation in Nespelem, Washington where the Chief continued to lead his people until his death on September 21, 1904. The Chief Joseph band of Nez Percé who still live on the Colville Reservation bear his name in tribute.

Bromide print of Professor Edmund S. Meany orating at the unveiling of the monument at Chief Joseph's grave on June 20, 1905. / Image via / Washington State University

9. Sacajawea, Tsi-ki-ka-wi-as (c. 1788-1812)

Lemhi Shoshone Tribe, Idaho

Bronze sculpture of Sacajawea and Seaman the Newfoundland, Merriweather Lewis' dog. Cascade Locks, Oregon. / Image via / Port of Cascade Locks

No listing of influential Pacific Northwest indigenous peoples would be complete without mentioning Sacajawea, the native woman instrumental to the Lewis and Clark Expedition to Oregon. She was only 16-years-old. Three years earlier she had been sold into a non-consensual marriage to Toussaint Charbonneau, a Quebecois trapper. Similar to Marie Dorion, Sacajawea also gave birth on the trail to her son Jean-Baptiste, but he survived.

When Merriweather Lewis and William Clark were making their way westward, they stopped to spend the winter of 1804–05 near a Mandan tribal village in present-day North Dakota. Here they found Sacajawea and Charbonneau who had taken her from her ancestral homelands near present-day Salmon, Lemhi County, Idaho. Knowing they would need the help of an interpreter who spoke the Shoshone language, Sacajawea and her husband were hired by Lewis and Clark to come along on the journey.

This decision changed the expedition in ways they could never have imagined.

Artists rendering of Sacajawea with Merriweather Lewis and William Clark. / Image via / Wikipedia Commons

Not only did Sacajawea prove invaluable as an interpreter, but she also became an accomplished guide on the journey. She saved the party on a few occasions, once from starvation by digging camas roots for the explorers to eat (they had been subsisting on tallow candles for food). Her son Jean-Baptiste delighted the men and kept their spirits up (Clark nicknamed him "Little Pomp" and later adopted him).

Perhaps her greatest role on the expedition was simply being a woman. Having a mother and child along for the journey demonstrated the peaceful intent of the explorers to other native tribes. While traveling through what is now Franklin County, Washington, in October 1805, Clark noted in his journal that "the wife of Shabono [Charbonneau] our interpreter, we find reconciles all the Indians, as to our friendly intentions a woman with a party of men is a token of peace." He went on to say that she "confirmed those people of our friendly intentions, as no woman ever accompanies a war party of Indians in this quarter".

Shoshone peoples.

After the expedition, Charbonneau and Sacajawea eventually settled near William Clark's home in St. Louis, Missouri. Historical documents suggest that Sacajawea died in 1812 of an unknown sickness, but Some Native American oral traditions relate that she left her husband Charbonneau, crossed the Great Plains, and married into a Comanche tribe. She was said to have returned to the Shoshone in 1860 in Wyoming, where she died in 1884.

William Clark's records dispute this. In his original notes written between 1825 and 1826, Clark lists the names of each of the expedition members and their last known whereabouts. For Sacajawea, he writes, "Se car ja we au— Dead."

Whether she passed away in Missouri at the age of 25 or went on to live a long life among her people, Sacajawea's legacy is alive and well today.

10. "Captain Jack", Kintpuash (c. 1837-1873)

Modoc Tribe, Oregon and California

Kintpuash in 1864. / Image via / Wikipedia

Kintpuash was born near Tule Lake, an area that now straddles the Oregon-California border. The ancestral homeland of the Modoc Peoples consisted of 5,000 acres until 1864 when they were forcibly removed by the federal government to the lands of their neighbors on the newly-created Klamath Reservation. The Klamath was a much larger tribe than the Modoc, and conflict was inevitable.

Now casually referred to as "Captain Jack" by white colonizers, Kintpuash stood firm. In 1865 he led a band of Modoc from the reservation back to their lands in California. Four years went by before the United States army rounded them up again and back to Klamath territory, but Kintpuash was undaunted. In 1870 he marched back home again with 180 of his Modoc kinsmen.

The government's outright refusal to allow the Modoc back into their homelands led to the outbreak of the Modoc War from 1872 to 1873.

Kintpuash fled with his band into the area now protected as the Lava Beds National Monument, and they settled into this natural fortress. His warriors made use of its many caves and trenches in the lava beds for defensive fighting, and women and children could be sheltered there. When the Modoc were finally located, the Army launched an attack on January 17, 1873. The US Army was beaten in this conflict but they weren't retreating either.

Captain Jack's Stronghold. / Image via / Wikipedia

Kintpuash's advisers suggested that the Army would leave if their warriors killed its leader General Edward Canby, (the future namesake of the town of Canby, Oregon) but Kintpuash hoped for a peaceful solution that would allow his people to stay in their territory.

It wasn't to be. During the next meeting of the peace commission on April 11, Kintpuash and several other Modoc broke down and drew pistols at a prearranged signal; he shot General Canby twice in the head. For this, he was executed on October 3, 1873.

The area of the Lava Beds National Monument where Captain Jack and his men held out against the United States Army is now known as Captain Jack's Stronghold. It took until 1984 for Kintpuash's skull to be returned for proper reburial by his Modoc descendants. He is buried at Fort Klamath Park, Oregon.

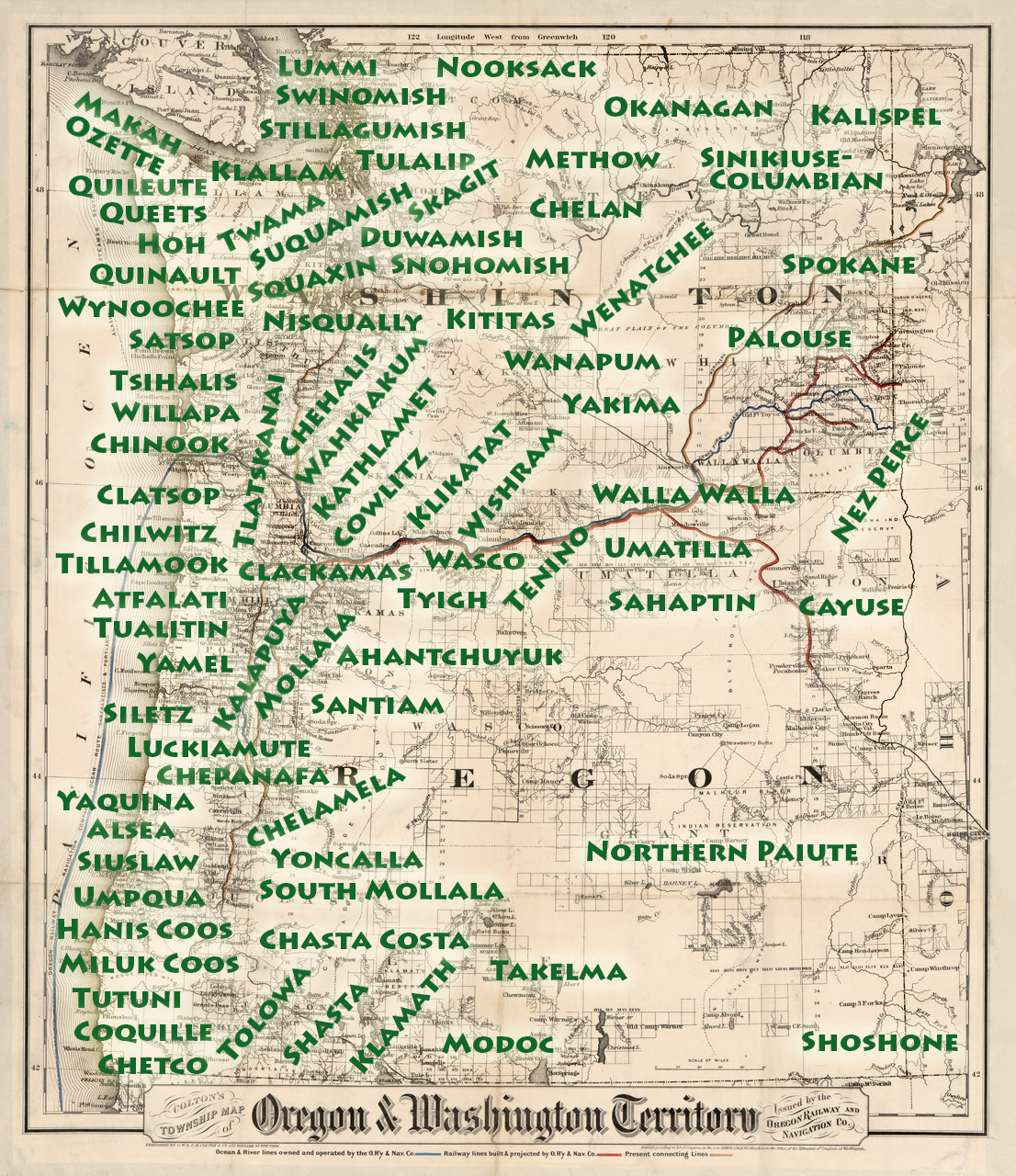

Approximate territories of the traditional homelands of many Oregon and Washington indigenous tribes. / Image copyright That Oregon Life 2021.