Deeper than the Grand Canyon, rich in Native legend, steeped in tragedy, and overflowing with fierce beauty, these are the untold stories of Hells Canyon in Oregon.

Along the Oregon-Idaho border lies Hells Canyon, North America’s deepest river gorge. At 7,993 feet deep, it carves nearly 2,000 feet deeper into the Earth than the Grand Canyon. Formed by the powerful Snake River and flanked by rugged cliffs and steep terrain, this massive chasm is a place of wild beauty. But beyond its dramatic and beautiful landscapes, Hells Canyon holds a long, complex, and often sobering history that continues to shape its identity today.

The Land Before Maps

The story of Hells Canyon starts with seven giant monsters. Nez Perce legend says that each year, seven giant monsters roamed eastward, eating Nez Perce children as they went. The tribe asked Coyote for help, and he teamed up with his friend Fox to stop them. Together they gathered animals with claws to dig seven deep pits right in the monsters' path, and then filled the holes with boiling, rust colored water. The giants fell into the holes and couldn't escape. As punishment, Coyote turned them into seven towering mountains (the mountains we refer to today as the Seven Devils). To be sure that the monsters couldn't trouble the Nez Perce anymore, Coyote split the land open between the Seven Devils and the Nez Perce, creating a deep chasm that the monsters couldn't cross. That chasm is Hells Canyon.

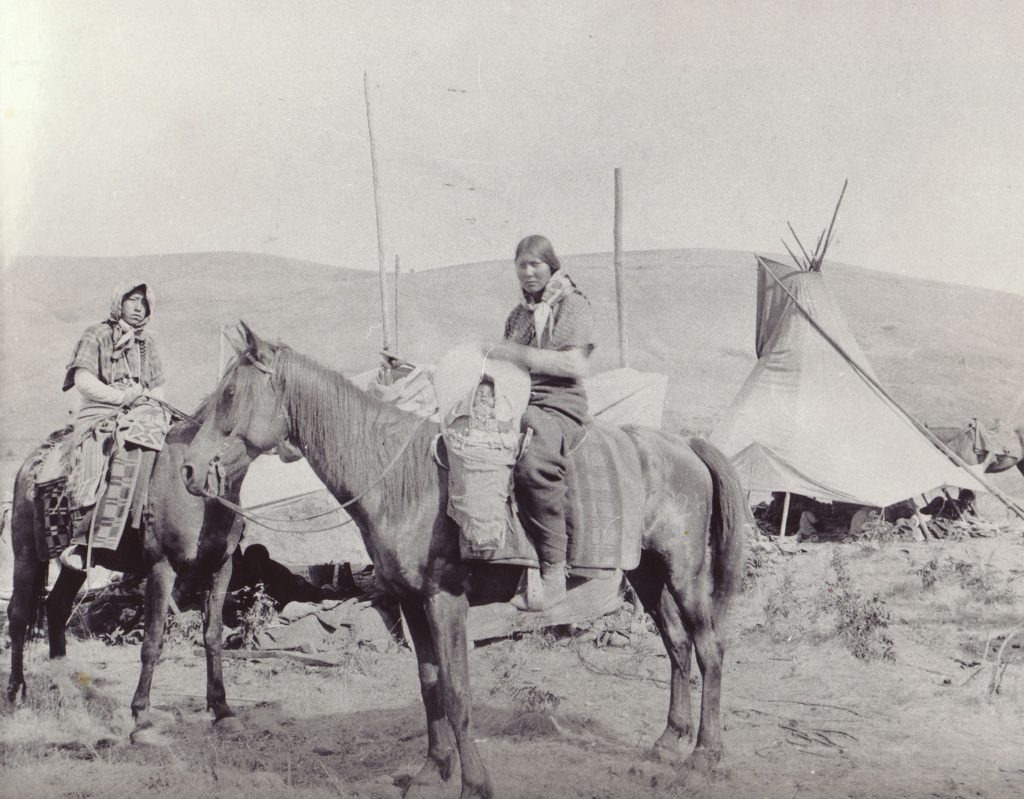

Long before white settlers came westward to Oregon, the Nez Perce (Nimiipuu) people were drawn by the region's salmon rich waters, mild winters, and thriving wildlife. They lived around and traveled through the canyon for thousands of years. Their connection to the land is still visible today through petroglyphs, ancient tools, and remnants of pit houses scattered throughout the area.

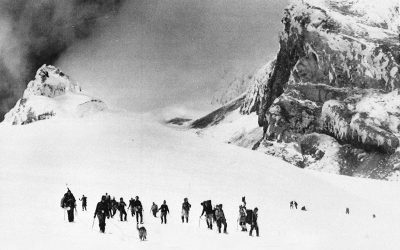

When European-Americans finally did start to come west, the Snake River’s deep gorge made the region hard to reach, which made early exploration slow. When a few members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition approached the canyon in 1806, they reported back with descriptions of rapids crashing against sheer rock walls. More explorers followed, including fur traders with the Pacific Fur Company in 1811 and Captain Benjamin Bonneville in 1834. Bonneville was both dazzled and frustrated by the canyon’s raw power, noting that its fierce beauty defied both pen and paintbrush.

Greed, Gold, And Tragedy In Hells Canyon

Nez Perce Forced Removal From The Hells Canyon Region

Hells Canyon wasn’t just rugged terrain, it was part of the ancestral homeland of the Nez Perce people who fished its rivers, followed seasonal game through its canyons, and considered the land around it sacred. For generations, the canyon and the nearby Wallowa Valley were core to their way of life.

That began to unravel in the 1860s, when gold was discovered, not in Hells Canyon, but near Pierce, Idaho, more than a hundred miles away. Even though that area was part of the Nez Perce reservation protected under the 1855 treaty, thousands of prospectors flooded in. Their arrival pushed the U.S. government to force a new treaty in 1863, often called the “Steal Treaty” by tribal historians. It slashed the Nez Perce reservation by more than 90%, and with it went legal claim to the Wallowa Valley and nearly all of Hells Canyon.

Chief Joseph’s band, who lived in the Wallowa Valley, refused to sign the treaty. They stayed on their land, believing the original 1855 agreement still stood. But as settlers moved in, tensions escalated. After years of pressure and broken promises, the U.S. Army ordered the Nez Perce to relocate to a much smaller reservation in Idaho. The band resisted. In 1877, after a series of deadly incidents involving settlers, a conflict broke out that would become the Nez Perce War.

Though the major battles didn’t take place in Hells Canyon, the land’s loss was one of the central injustices that sparked the conflict. The forced removal and the four month long bloody flight as the non-treaty Nez Perce fled towards Canada were part of a larger pattern of land seizure, betrayal, and displacement that reshaped the region and left scars that still run deep today.

Gold And Death In Hells Canyon

In the years that followed, white miners encouraged efforts to bring steamboats through the canyon. Most of those attempts ended in wreckage, as the Snake River proved nearly impossible to tame.

During the mid-1860s, Chinese miners began working claims in the area. They took on the hardest, most isolated jobs, often in places no one else would go. Then in 1887, tragedy struck. Near Deep Creek, as many as 34 Chinese laborers were ambushed and killed by a group of men from Wallowa County. The victims were mutilated and their gold was stolen. Despite the scale of the crime, there was no real investigation, and no one was held accountable. The massacre is one of the deadliest crimes against Chinese immigrants in American history, and its legacy still lingers in the region’s collective memory.

Hells Canyon In Modern Times

Power Struggles And Preservation In Hells Canyon

Even as transportation and technology advanced, Hells Canyon resisted full-scale development. Its steep, narrow shape kept railroad companies out, and few roads or bridges made access any easier. In the 1940s, federal planners proposed the Hells Canyon High Dam, an enormous hydroelectric project that would have flooded the canyon and eliminated salmon runs upstream. But private energy companies fought for control. Idaho Power ultimately won and constructed three smaller dams: Brownlee, Oxbow, and Hells Canyon, completed between 1958 and 1967.

A new push for a fourth dam in the 1960s reignited debate. This time, the question reached the U.S. Supreme Court. Justice William O. Douglas, familiar with the area, questioned whether more dams were worth the environmental and cultural loss. His opinion helped turn the tide, and the idea of preserving the canyon began to take hold.

By 1975, the effort to protect Hells Canyon became law. Congress established the Hells Canyon National Recreation Area, safeguarding over 660,000 acres of wilderness and 62 miles of the Snake River. It was a significant shift from a place seen as a barrier or a resource to one recognized for its natural and historical value.

Today the Nez Perce work to protect the Snake River’s health through environmental advocacy and legal action. In recent years, the Tribe reached a settlement with Oregon to address mercury pollution and restore salmon runs impacted by the Hells Canyon Complex dams.

Recreation In A Canyon Like No Other

While its past runs deep and dark, today Hells Canyon draws visitors for reasons that are more light-hearted. Hikers and backpackers can explore around nine hundred miles of trails, although many are remote and rugged. Horseback riders find open terrain and quiet solitude. Jet boat tours offer a thrilling way to experience the Snake River up close, carving through the steep canyon walls.

Scenic viewpoints on the Oregon side offer dramatic vistas. The Hells Canyon Overlook is the most accessible, with paved parking and interpretive signs. For those willing to brave a tougher drive, the Hat Point Overlook rewards with views of the Snake River and the Seven Devils Mountains. Saddle Creek Campground, located nearby, offers a great place to pitch a tent and take in the expansive landscape. You can check out our full adventure and camping guide to Hell's Canyon here.

Despite its difficult past and challenging geography, Hells Canyon stands today as both a natural wonder and a place of reflection. Its immense depth is matched only by the layers of history that lie within it.