The rising waters of lakes and reservoirs have submerged many budding Oregon metropolises over the years, from tiny one-horse towns to an entire Native American homeland.

Postmistress and Robinette Store owner Francis Carrithers with her daughter, Diane, and their dog, Tojo, in front of the family store in the early 1950s. (Image: Baker County Library)

Since well before the time of Plato’s story of Atlantis, storytellers all over the world have had a special fondness for legends of cities and civilizations that, at the peak of their prowess, were suddenly lost beneath the waves of the sea, leaving only a misty legend and maybe — if a diver knows just where to look — maybe some ghostly underwater ruins.

Well, Oregon certainly can’t claim to be hiding the lost continent of Lemuria or the lost city of Atlantis beneath the placid surface of Fall Creek Reservoir or something like that. But in the mid-20th century, when dams were built all over the state to create hydroelectric power and tame the unruly and flood-happy rivers, the lakes that formed behind them did cover up some thriving Oregon towns. By taking a few liberties with the dictionary definition of “city,” we can, with a more or less straight face, dub these vanished communities the “Lost Cities of Oregon.” And one of them, in particular, almost qualifies for real as a “lost civilization.”

Here are a few of them:

Klamath Junction

In the late 1950s, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation got to work on a dam project on Emigrant Creek, a few miles south of Ashand. There was already a dam on the creek, a 110-foot-high structure built by the Talent Irrigation District in 1924, which backed up a tidy little irrigation-and-water-supply reservoir there; next to the reservoir stood the little town of Klamath Junction, with two gas stations, a dance hall, some homes and a cemetery.

In 1960, the Bureau had finished its work, and a new 204-foot dam stood where the old 110-footer had stood, and the waters of Emigrant Creek were slowly filling the new impoundment — and lapping at the foundation walls of the now-abandoned town of Klamath Junction.

Today, if you know where to dive, you can actually look around the ruins of the Lost City of Klamath Junction. One young snorkeler reported seeing a gumball machine at an old gas station — although what she was looking at was more likely a glass-topped Esso gas pump. (It should go without saying that exploring underwater structures is extremely dangerous. Don’t do that.)

Robinette

The busy industrial town of Robinette, on the banks of the Snake River, in

the mid-1950s. (Image: Baker County Library)

The town of Robinette, out near Baker City, was originally intended to be a big railroad facility, and although it never reached big-town levels, it was regionally pretty important. By the 1920s, it was the terminus of the railroad line, so that’s where area farmers and producers had to bring their goods to access the rail network. It boasted a general store, a train depot, a schoolhouse, and several residences, along with a hotel. It also was, at various times, home of several different timber-industry facilities and even a Standard Oil plant.

All of this vanished beneath the waves of Brownlee Reservoir in 1958 after the Idaho Power Company built a 420-foot dam with power station on the Snake River there.

Lookout Point reservoir: A lost Suburbia

Along the Middle Fork Willamette River, midway between Eugene and Oakridge, once lay a collection of small towns and communities that were destined to become Lost Cities. They included Landax, Eula, Lawler, Signal, Reserve and Carter.

Landax and Eula were probably the biggest of these towns; both had their own grade schools until 1940, when they were consolidated at Lowell.

The towns’ last days in the sun came in the early 1950s, when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers completed Lookout Point Dam. One source says the towns were all razed before the flooding, which is certainly possible, since everything would have been made of wood and probably floated off if allowed to do so; but there almost certainly were a few cement structures too, and beneath the waters of Lookout Point Lake, those structures are still there — although probably covered with silt by now.

These little hamlets are like all the other towns that have slipped beneath the waves of reservoirs and lakes in Oregon, except maybe Robinette — tiny, unimportant, ill-remembered, largely unlamented. There is, however, one that was none of these things. Its story is one that, in many ways, comes close to the legend of Atlantis — uncomfortably close.

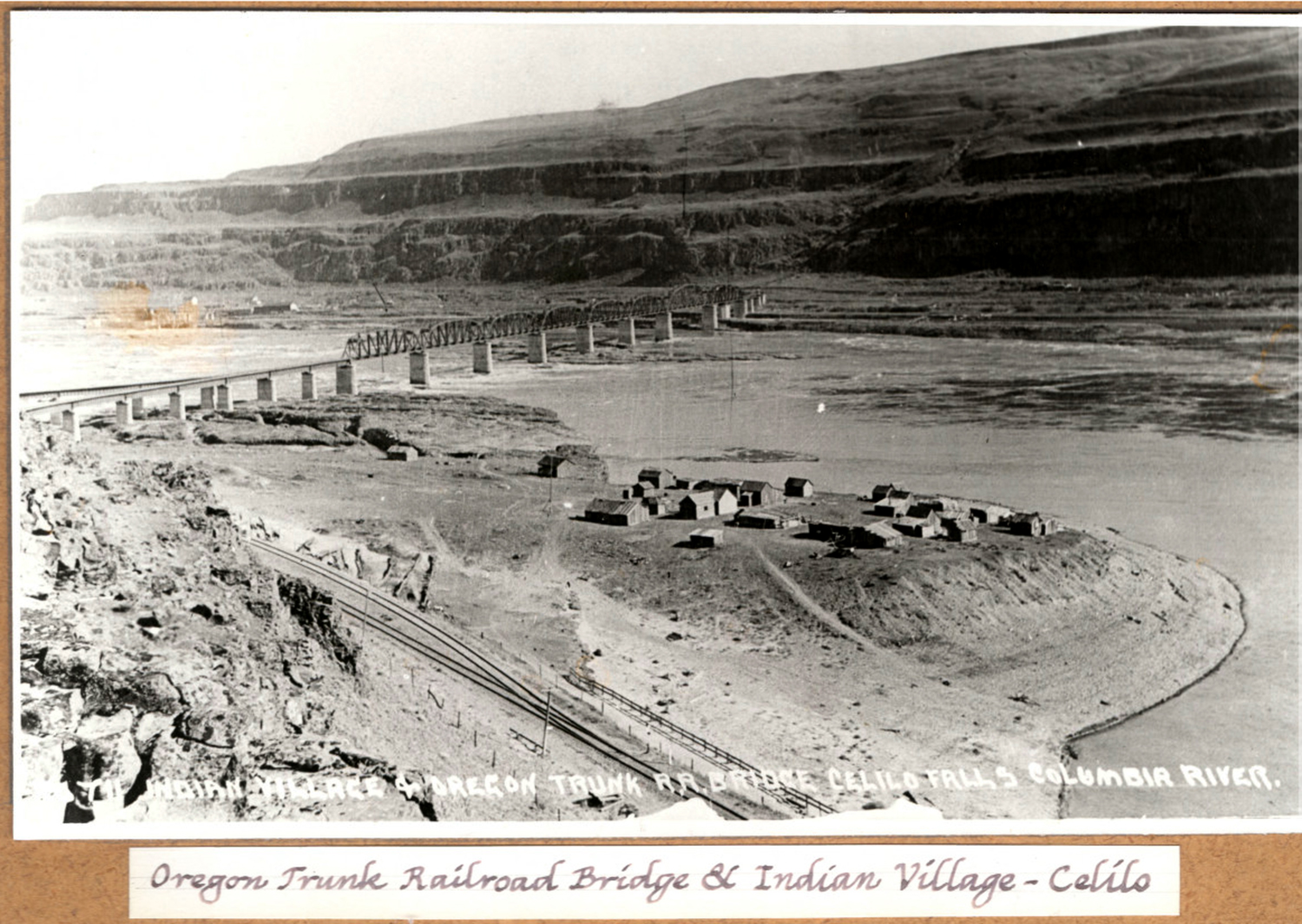

Celilo: A lost nation

Part of the Indian village at Celilo Falls, as it appeared in 1915 or so. (Image: Columbia Gorge Discovery Center)

The story of the sacrifice of Celilo Falls, one of the great natural wonders of Oregon, to a growing nation’s thirst for hydroelectric power, is a story that’s been told well and thoroughly many times (including here in an Offbeat Oregon column). As is always reported, the flooding of the falls removed the local Native Americans’ fishing grounds, and with it a key part of their culture. One thing that’s often not mentioned, though, is the loss of their actual homeland.

When Celilo Lake rose and flooded the lands around the falls, it basically rendered the local Indians homeless, flooding their village as well as the ancestral land on which they lived.

After it was flooded out, Celilo Village was relocated, sort of — but no, not really. Actually, it was replaced — replaced with a brand-new compound built at minimal expense near the edge of the lake that covered what had once been their land.

Celilo Falls with some of the Native American buildings and campsites in

the foreground, photographed in 1903. The more permanent structures

were located further up the riverbank, in locations less susceptible to

seasonal flooding. (Image: Moorhouse/ UO Libraries)

Other towns that were moved to make way for reservoir impoundments, such as Lowell, were conserved as much as possible; houses were moved or their owners were paid off, and the new town grew as the old town had done. The new Celilo Village, though, was built for the Indians by the Army Corps of Engineers at the behest of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The result was something that looked a lot less like home than the old village. In fact, it more resembled a prison or a military base. It was cut off from the river by the highway and the railroad, both of which it was quite close to. Not surprisingly, it soon got to looking very ramshackle indeed.

In 2006 residents got some much-needed improvements to the village courtesy of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers — in particular, a great new longhouse, along with some improvements to the water and sewer systems (all served up with some appallingly tone-deaf grumbling from certain BIA officials, who seemed to feel the reason the village was so awful was that the Indians didn’t take enough pride in their residences there.)

But if you were to ask the residents, most of them — those old enough to remember — would tell you they’d trade it all in a heartbeat for their old village, now seemingly lost forever under the placid surface of someone else’s lake.

(Sources: McArthur, Lewis A. Oregon Geographic Names. Portland: OHS Press, 1992; Medford Mail Tribune, 23 Aug 2012; Silver, Jon. “Tiny tribal village ...,” Daily Journal of Commerce, 21 Sep 2006; ci.lowell.or.us)

This article was was used with permission and originally published at offbeatoregon.com.