Every spring, on the Oregon Episcopal School campus in southwest Portland, there’s a day that doesn’t feel like a normal school day. People gather. A bell tower stands quiet and tall. A few words are spoken, then names are read—slowly, carefully—like each syllable matters. After each name, a bell answers.

It’s not ceremony for ceremony’s sake. It’s remembrance for something that Oregon hasn’t really forgotten, even if time has tried to move on: the Mount Hood climb of May 1986.

A required adventure, a familiar mountain, and a plan that seemed manageable—until it wasn’t

In the mid-1980s, Oregon Episcopal ran an outdoor program built around the idea that challenge can shape character. The model borrowed from Outward Bound: put teenagers in the kind of environment that demands teamwork, judgment, and grit. Train them well. Equip them properly. Let them discover, in the most literal sense, what they’re capable of.

Mount Hood—11,249 feet, a snowy icon in the center of Oregon’s Cascades—was part of that tradition. It wasn’t a remote Alaskan peak. It was “our” mountain. A place people could point to from Portland on a clear day.

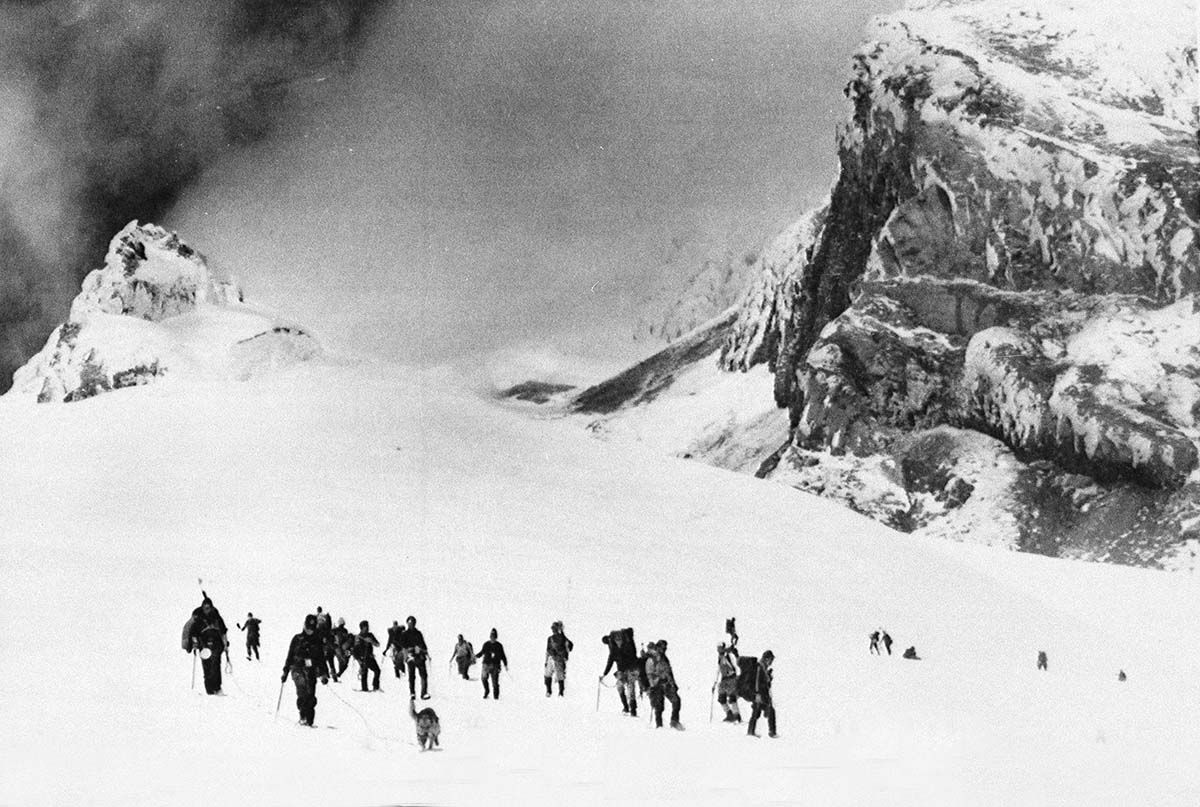

On Mother’s Day weekend, May 11–12, 1986, one of the scheduled student groups prepared for their summit attempt. Late that evening, teenagers gathered at school with packs, harnesses, ropes and slings, crampons, tarps, stove, first-aid kits—the whole inventory of a serious snow climb. At Timberline Lodge they’d pick up ice axes and helmets. The goal was ambitious but not unheard of: start in the night, reach the summit, and return within a long push.

There were twenty people connected to that expedition: fifteen students, a parent, a school chaplain, an administrator, and two experienced climbing professionals who would join at Timberline.

Within days, nine of them would be dead.

The adults they trusted—and the weather that didn’t care

The trip’s key adult figure was Tom Goman, a priest and longtime school leader who also carried a reputation as a competent climber. Students liked him. Many trusted him instinctively. On school trips, that trust can become the whole emotional foundation of safety: “If he says we can do this, we can.”

But Mount Hood has a way of shrinking certainty.

Forecasts for that period were grim—storm conditions building, high winds, heavy moisture. Anyone who’s spent time around Hood knows how fast it can change. One minute you have a route; the next minute you have a spinning white room where “up” and “down” start feeling like guesses.

The group started up in the early hours—around 3 a.m.—from the Timberline area. Initially conditions didn’t seem catastrophic. Snow underfoot, cold, but workable.

As morning came on, a few climbers began to question whether pressing higher was wise. And that’s one of the most haunting details of the whole story: some people listened to their bodies and their instincts and turned around—just early enough.

One student, feeling sick, headed down with her mother. Two more students returned from higher up after deciding they weren’t okay. Later, another climber left the group alone, experiencing snow blindness. Little by little, the party thinned.

The main group—thirteen people—kept pushing upward.

A turning point that came too late

Somewhere high on the mountain, as the weather worsened, the decision finally shifted from “we can summit” to “we have to get out of here.”

But timing matters on Hood. When a real storm arrives, it doesn’t politely wait while you reorganize.

Visibility began collapsing. Wind increased. The mountain’s normal landmarks—the things people use to keep bearings—were erased. Under those conditions, a person can become disoriented in steps, not miles. You don’t just lose the route. You lose the world.

Then the expedition’s fragile balance tipped further: the youngest student in the group started showing signs of dangerous cold stress. He slurred his words. He stumbled. He wanted to sleep. In the mountains, sleep can be the final lie hypothermia tells.

The group did what humans do when they care: they stopped, and they tried to save him.

They put him in the only sleeping bag. A student climbed in with him to share warmth—an act of courage that cost more than anyone understood in the moment. Hot water was made. Sugar was dissolved into it. He drank. His temperature improved enough that they could move again.

But the hour they spent rewarming him was an hour the storm used to tighten its grip.

The wrong direction, the false sense of “down,” and the terror of not knowing where your feet are

In that kind of whiteout, even moving downhill can turn into sideways drift. A slight error becomes a wide error. And when you can only see a few feet—or less—every step feels like it might lead into nothing.

At some point, the group’s navigation went wrong. Instead of angling safely toward their intended descent line, they ended up crossing the mountain’s face. The terrain grew more dangerous. Cracks appeared in the snow—warnings of crevasses or unstable features near glaciated areas.

One of the guides, Ralph Summers, recognized enough risk to make a decision that likely saved whoever could still be saved: stop moving and build shelter.

Around 7 p.m., with the group exhausted and unsure of their exact location, he began digging a snow cave.

A snow cave can be a miracle—if it stays open, if it stays dry enough, if it’s sized for the number of bodies inside, and if the storm doesn’t bury it like a closed fist.

A snow cave meant for survival—packed beyond its limits

The cave they carved out wasn’t built for thirteen. It couldn’t be. It ended up cramped, wet, claustrophobic. Body heat began melting the interior walls. Slush pooled on the floor. Breathing felt thin and anxious.

Outside, the wind was savage.

They rotated people at the entrance and outside, trying to keep the opening clear. But even that became a losing battle. Gear was pulled away by the storm. Snow drifted and refroze. The entrance narrowed.

Inside that small space, teenagers waited while a mountain tried to erase them.

The desperate walk for help

By Tuesday morning, it was clear the group could not simply “hold on” and hope the weather passed fast enough. Summers made a call no one wants to make: someone had to leave the cave and try to find help, even if that person didn’t come back.

One student, Molly Schula, went with him.

They stepped into the whiteout and began moving—down, they believed. But even then, the mountain had them. They reached not Timberline, but Mount Hood Meadows—two miles east. That detail alone tells you how thoroughly the storm scrambled the climb’s geography.

Still: they found people. They got help moving. They lived.

Back in the cave, the remaining eleven fought to keep air moving through an opening that was steadily being sealed by fresh snow.

The search: heroic, dangerous, and agonizingly uncertain

When the group was reported overdue, volunteer rescue teams gathered at Timberline in conditions that were themselves life-threatening. Winds were extreme. Snow was measured in feet. Helicopters were limited by visibility. Ground searchers could barely stand, let alone cover a huge alpine slope.

They searched anyway.

Hours became days. Names turned into faces in parents’ minds. Every rumor felt like oxygen; every correction felt like falling.

When weather finally began to break, rescuers found three students outside the cave, their bodies curled in the snow as if they had tried to make themselves smaller against the cold. The discovery briefly created confusion—some early communication suggested “survivors,” a word that ripped open hope and then, cruelly, had to be taken back.

Search teams kept probing, sweeping lines across the slope, pushing long poles into the snow over and over again, listening for the hollow hint of a void.

Late on Wednesday—near the end of the day—an avalanche probe hit something solid.

They dug.

The cave was there.

Inside were faint sounds. A living voice. A moan.

Two students were found alive, their core temperatures so low that survival felt almost impossible. Doctors across Portland threw everything they had at the injuries and hypothermia—treatments that require an enormous amount of staff, equipment, and luck. Those two survived. Others did not.

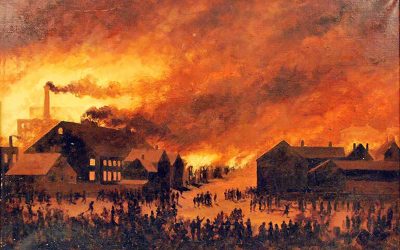

In all, nine people died: seven students and two adults.

What the tragedy became: grief that didn’t end, and a community that had to learn a new language

In the immediate aftermath, questions flooded in—how could this happen, who is responsible, what decision sealed their fate, what should have been different?

Investigations followed. Lawsuits followed. Anger followed. And so did something else: the slow, imperfect work of integrating grief into life.

Some survivors built careers around helping others. Some families became devoted to grief support work. The school ended the kind of Mount Hood expedition that had been normal before 1986. And every year, back on that campus, the day arrives again: bells, names, silence, service.

Because that’s what tragedies like this do. They don’t remain “a story from 1986.” They become a thread in the identity of a place—and a warning written in wind and snow on a mountain that still stands above Oregon, beautiful and indifferent.

Much of what we understand today about the decisions made on the mountain comes from later investigations and in-depth reporting, including a detailed 2018 feature in Outside Magazine.