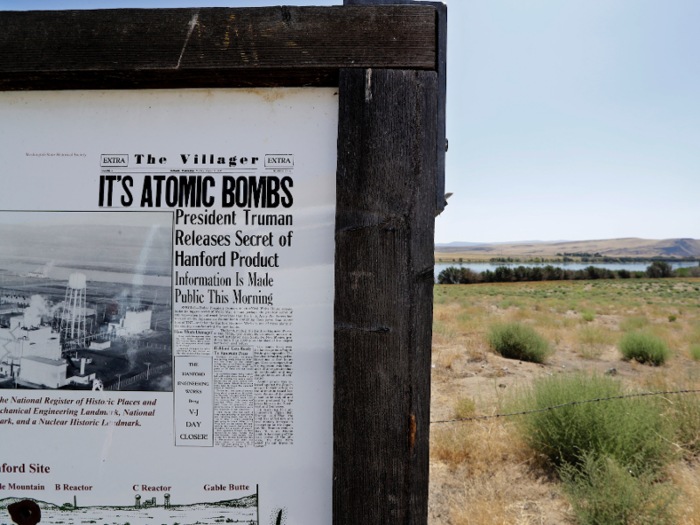

While Christopher Nolan's "Oppenheimer" brilliantly captures the ethical dilemma surrounding nuclear weaponry, the film overlooks the ensuing devastation caused by Hanford's lethal nuclear byproducts. Hanford is, in fact, only given a movie-mention one time in the three hour epic, and that's simply not enough. From 1944 up to the Cold War's conclusion in 1991, Hanford provided over 60% of the plutonium for the country's nuclear weapons program, sufficient for several tens of thousands of arms in the US nuclear stockpile.

The history behind the Hanford site is absolutely terrifying. Even more horrific is the contamination risk left behind and still growing. Today, Hanford, Washington, only 35 miles from the Oregon border, is considered to be the most toxic site in the US.

Before the 1940s and the grim reality of the Second World War, life near a bend of the expanse of the Columbia River was rather idyllic. Folks in the communities of White Bluffs and Hanford, Washington grew peaches, grapes, and wheat. They raised sheep, cattle, and their families in the high desert land. Long before this, the arid plain was the traditional winter home for several Native American tribes, who to this day maintain treaty rights to hunt and fish along the river.

Enter The Manhattan Project

Everything surrounding nuclear research in the late 1930s was the most heavily guarded clandestine secret of the era. Little was known about the deadly effects of splitting a minuscule atom, but the US military was determined to find out via research they code-named the Manhattan Project. More specifically, the race to produce the world's first nuclear weapon. Conjecture turned to fact and Hanford's fate was sealed in 1940 when the first particles of Plutonium were created. Specifically, the isotope plutonium-239 is what the military was after.

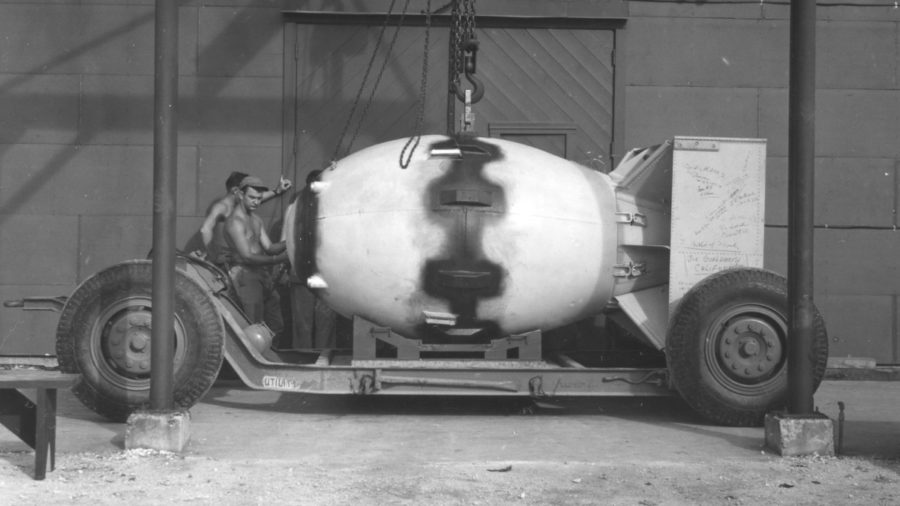

Physicists at the then top-secret labs in Los Alamos, New Mexico already had plans drawn up for a nuclear bomb they dubbed the "Fat Man" due to its bulbous structure. It was a plutonium-based weapon, while its cousin "Little Boy" was uranium-based. Both were life-ending.

Uranium is needed to produce plutonium, its mother-element, so to speak, and massive quantities of refined plutonium-239 would be needed in the race to produce a war-ending bomb. In that era, the mere existence of element 94 was taboo. Classified documents of the time referred to plutonium with the code words “49” or “product.”

The Columbia River Site of Hanford was Selected in 1943

In February 1943, the US government forcibly seized 670 square miles of desert in southeast Washington. They did this by "condemning" the land just north of Richland, WA that encompassed the small towns of Hanford and White Bluffs. Not dissimilar to events in Oregon's Scoggins Valley 30 years later, residents were given the ultimatum to pack up and move within 30-90 days.

Their homes were torn down and fruit orchards pulled up by the roots. Even the dead were forced to leave; their bodies were exhumed from the town cemetery and reburied in nearby Prosser. The Army broke the Treaty of 1855, informing the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakima Nation, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, the Nez Perce Tribe, and Wanapum that their hunting and fishing rights would be restricted and eventually revoked.

What were once thriving small communities in rural America were effectively wiped off the map.

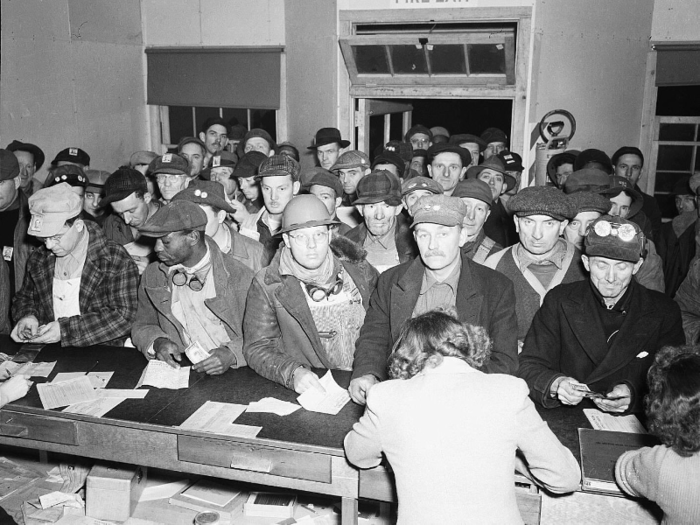

The project brought an influx of residents to the area, with Richland’s population soaring from fewer than 300 to more than 11,000 people. Workers were not informed of what they would be building or why. At that time "aiding the war effort" was enough of an explanation. Patriotism was high while jobs were scarce. "Don't ask, don't tell" was the enforced mentality at the Hanford Site. Until the first bomb was dropped on Japan, people performed their jobs never knowing what they were actually building.

Hanford, Washington Became Home to the World’s First Production-Scale Nuclear Reactor

Only a select few elites knew the truth of what was being built in Washington State. The general public would have no inkling for another two years.

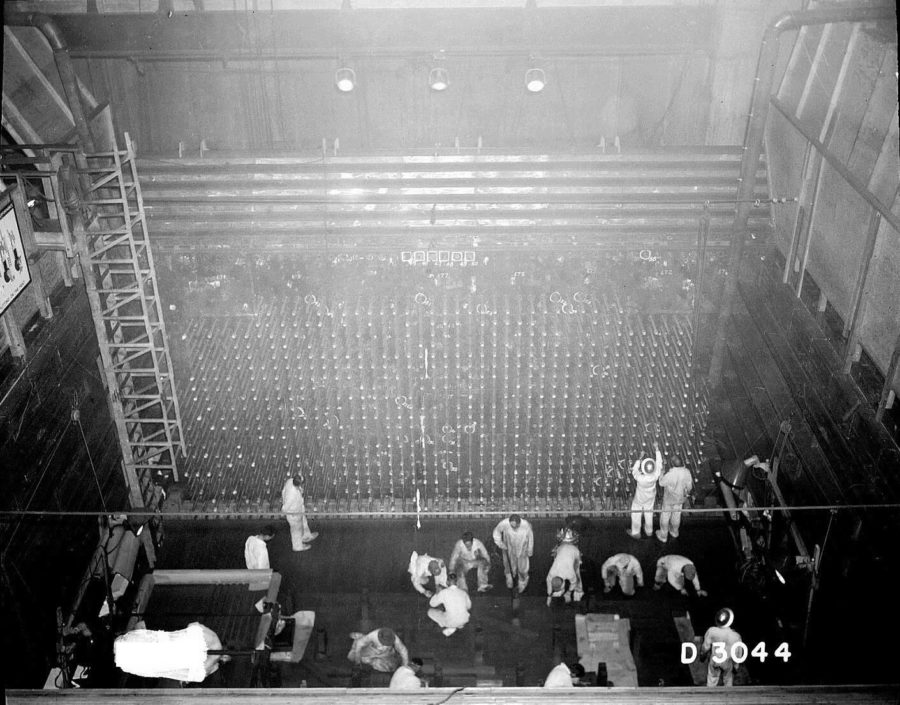

Manufacturer DuPont began advertising for workers in newspapers for an unspecified "war construction project" in southeastern Washington, offering an "attractive scale of wages" and cozy living facilities. Before the war ended in 1945, The Hanford Engineer Works successfully constructed 554 buildings, three nuclear reactors, and three 820 ft. plutonium processing canyons. The project required 386 miles of roads, 158 miles of railway, four electrical substations, and 780,000 cubic yards of concrete.

Construction of the B Reactor began in August 1943 and was completed on September 13, 1944. The reactor produced Hanford's first plutonium on November 6, 1944. The 1.5 lbs. of paste-like material was packed into a lead box and sent by car to Portland, Oregon, where it went on by passenger train to Los Angeles. From there it was picked up by a US Army officer from Los Alamos. The man was never informed that he was guarding a payload of highly radioactive substance.

By April 1945, shipments of plutonium were headed to Los Alamos every five days.

Plutonium Produced at Hanford Was Used in The First Nuclear Weapon, and Eventually in the Bomb Dropped on Nagasaki, Japan, August 9, 1945.

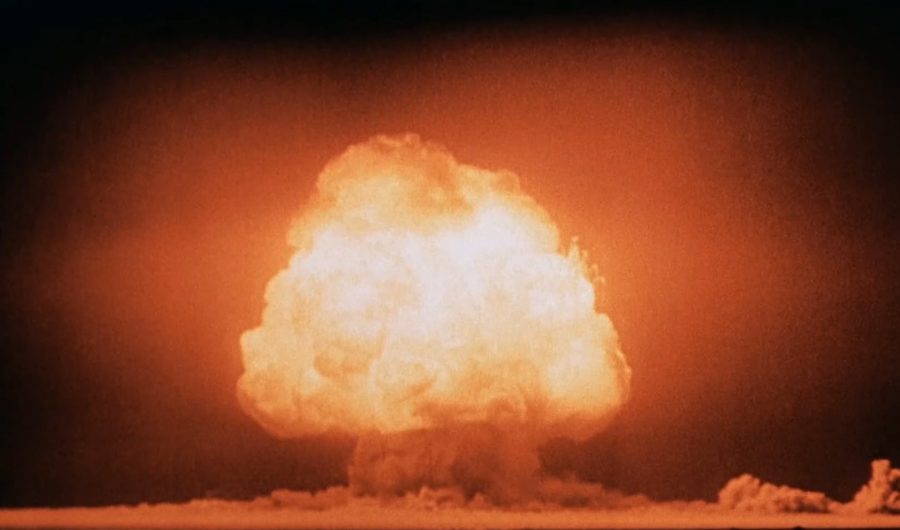

On July 16, 1945, in a remote desert location near Alamogordo, New Mexico, the Trinity Test commenced, powered by the plutonium from Hanford, Washington. It was the world's first detonated nuke, creating an enormous mushroom cloud some 40,000 feet high and ushering in the new Atomic Age. As physicist Robert Oppenheimer watched the bomb go off, he disconcertingly thought, "I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds."

On August 6, 1945, the uranium bomb "Little Boy" was dropped over Hiroshima, Japan, taking between 90,000 and 146,000 human lives with it. Three days later "Fat Man" packed with its load of Hanford-produced plutonium detonated over Nagasaki, killing an additional 39,000 to 80,000 people over the next four months.

In 2010, Robert Alvarez, a former Energy Department official, said enough plutonium was buried at Hanford to create 1,800 bombs the size of what was detonated on Nagasaki.

After WWII Hanford Still Continues to Poison

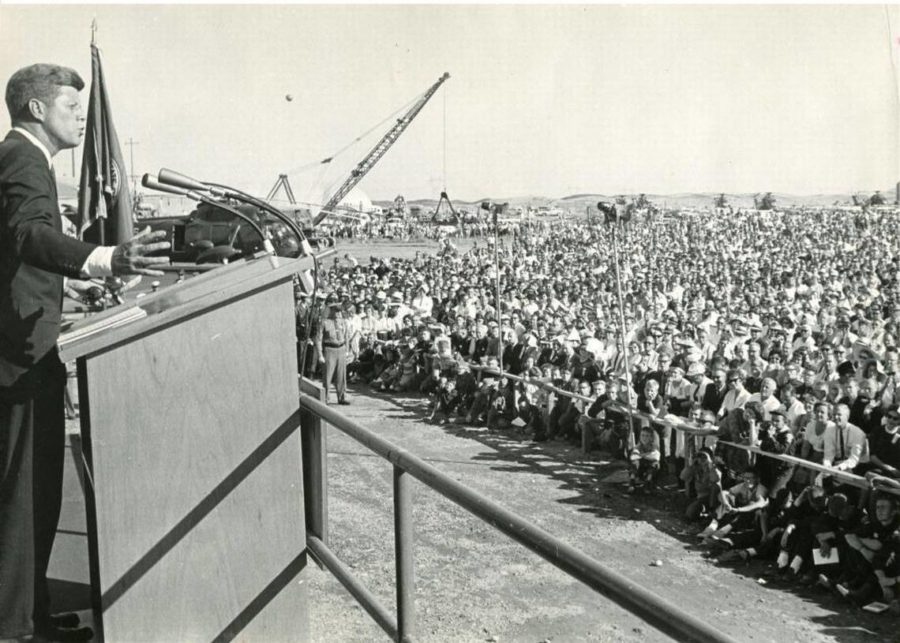

Production of weapons-grade plutonium never ceased at the Hanford Site, even after the war officially ended. Realizing new threats from Soviet-era Russia, manufacturing continued under the Atomic Energy Commission to produce a total of 57 tons of the grayish metallic substance. This was enough to arm the majority of the 60,000 weapons in the U.S. arsenal.

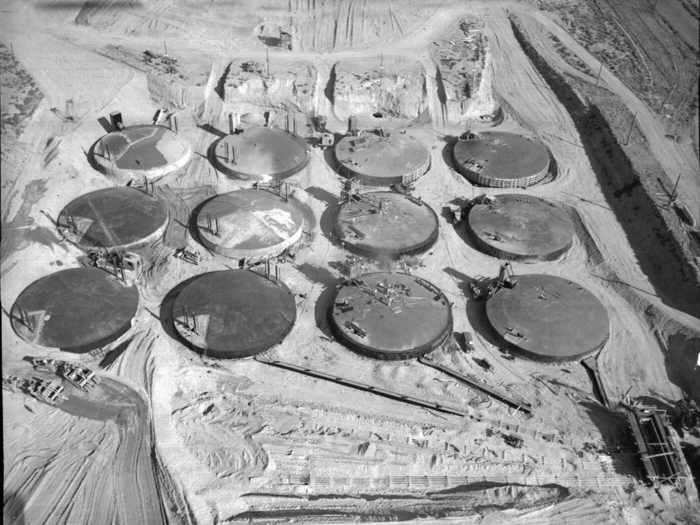

Individually, the nine reactors at the site possessed a life expectancy of 22 years. Decommissioning began in 1963 and was largely completed in 1987 with the shut down of "N", the last reactor still in operation. Since then, most of the Hanford, Washington reactors have been entombed (or "cocooned") to allow the radioactive materials to decay, and the surrounding structures have been removed and buried.

Unfortunately shutting down anything nuclear does not equal "safe". The ecological nightmare of 56 million gallons of toxic waste at Hanford is a bleak reminder of this reality.

Signs of Hanford's impact on the environment were noticeable as early as 1960, when a 55-foot whale, killed off the coast of Oregon, was radiating gamma rays. Scientists suspected it had eaten irradiated plankton contaminated from waste products that had floated down the Columbia River into the sea.

In 1989, the Tri-Party Agreement was signed by the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Energy, and the Washington State Department of Ecology to clean up Hanford's mess.

In April 2021 an Underground Hanford Storage Tank Was Discovered to be Leaking Radioactive Liquid Into the Ground.

As reported by The Oregonian earlier this year, tank B-109 is seeping some of its 123,000 gallons of radioactive waste into Central Washington land. The giant tank was constructed during the Manhattan Project and received waste from Hanford operations between 1946 to 1976. Not only does this spell trouble for our northern neighbor, but things could also quickly turn ugly for Oregon and Idaho.

In a disturbing new article by literary journal Virginia Quarterly Review, author Lois Parshley writes in extreme detail about the danger levels still present at the site.

60% of Hanford, Washington Employees Have Reported Toxic Exposure and High Cancer Rates

The article also caught the attention of The Oregonian. Douglas Perry breaks down some highlights of the VQR article in his October 2021 piece, citing the "growing risks to entire Northwest region".

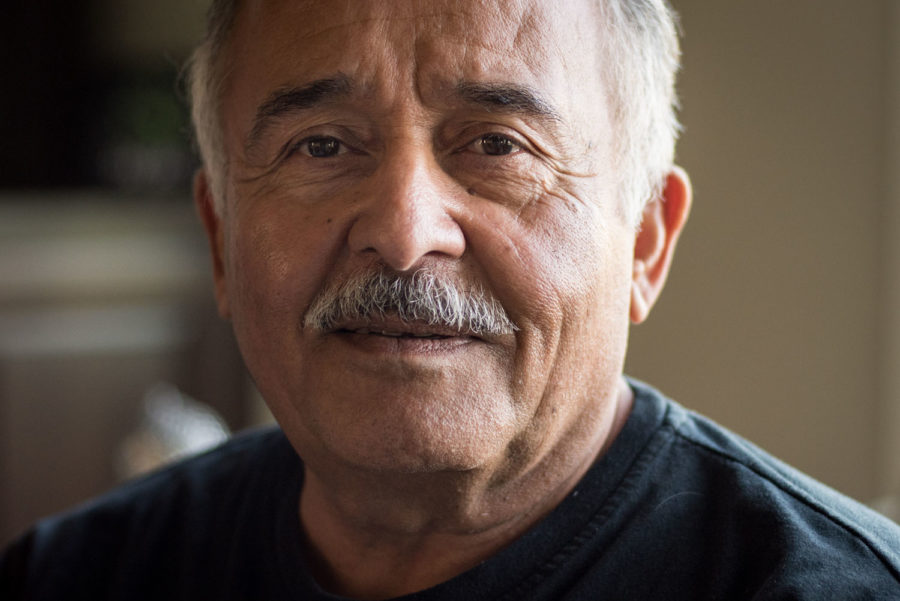

Hanford technician Abe Garza is interviewed by the VQR. “Shortly after he arrived at the worksite, [Garza’s] nose started bleeding, and wouldn’t stop,” Parshley writes. “Another crew member complained of a terrible headache. A third said he could smell something like onions. (Previous chemical exposures at work had destroyed Garza’s ability to smell.) Garza knew right away something had gone wrong, but it was already too late: A potentially lethal cloud of chemicals was sweeping over them.” Garza was later diagnosed with heavy-metal poisoning -- as well as toxic encephalopathy, a dementia-like condition that often proves fatal. (The Oregonian)

Garza was performing a routine inspection of the site’s holding tanks in 2015. “The amount of high-level waste currently in just one of Hanford’s 177 tanks would cover a football field to a depth of one foot. More than a third of the single-shell tanks have already leaked. One of the double-shell tanks, into which waste was moved after concerns over leaks, has also failed. In late April of 2021, news broke about a new leak in one of the single-shell tanks, which is estimated to be spilling nearly 1,300 gallons a year." (VQR)

An astonishing 60% of Hanford, Washington employees have reported some level of toxic exposure. More terrifying is the amount of radioactive waste and gas, seeping into the groundwater and contaminating the very air.

A 2002 study found that Native American children from the Hanford area have “an extremely elevated risk of immune diseases.” Cancer is also exceptionally prevalent among residents of the area.

What Can Be Done? Namely, What is the US Government Doing to Facilitate the Cleanup Process at Hanford?

The Hanford Site is roughly 230 miles from Portland and a scant 35 miles from the Oregon border. Our state has a tremendous stake in what continues to happen in efforts to clean up Hanford's disastrous mess.

In a 2019 report, the Department of Energy extended its timeline for cleaning up Hanford’s radioactive sludge until 2100.

Faced with rising costs, the US DOE announced that it would redefine what constitutes “high-level radioactive waste” under federal law, which would allow it to leave additional waste in place, rather than transferring it to safer, long-term storage. The DOE estimates that this relabeling could save the agency between $73 and $210 billion. When applied to Hanford, Washington, it would allow the tanks holding nuclear waste to be filled with concrete and left where they are, after which the DOE has promised a 100-year-long monitoring period.

A century of monitoring might seem like enough, but the timeline of nuclear contamination is measured on a much different scale. Even after the monitoring period, some of Hanford’s waste will still be radioactive.

Tom Carpenter is the executive director of HanfordChallenge.org, a group that aims to "create a future for the Hanford Nuclear Site that secures human health and safety, advances accountability, and promotes a sustainable environmental legacy."

“If you inhale strontium-90,” says Carpenter, referring to a radioactive particle widely found around Hanford, “and it kills you, and you’re buried in the ground, those radionuclides will persist around your grave.” He added: “They can get into food supplies again. They essentially never go away.”