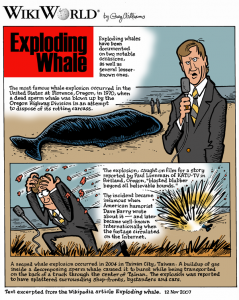

What do you do when an 8 ton whale washes up on shore? You blow it into a million stinky little whale pieces of course. This is the story that some of you may know, which took place in Florence, Oregon about an inexperienced highway engineer who thought the most logical thing to do with the 8 tons of rotting whale carcass was to obliterate it. Unfortunately, he guessed wrong about how much dynamite would be needed.

On Thursday, Nov. 12, 1970, an event happened that put the town of Florence on the map. A highway engineer, faced with the need to dispose of an eight-ton whale carcass which had washed up on the beach, tried to vaporize it with a half-ton of dynamite, with results that most people who know about dynamite could have predicted — and did.

A whale of a deal

on a new Oldsmobile!

Walt Umenhofer sure saw it coming. He was a businessman who happened to be in town with his brand-new car, an Oldsmobile 88 Regency, which he later told Springfield News reporter Ben Raymond Lode that he’d bought days earlier at Dunham Oldsmobile in Eugene during a promotion taglined — no, really, I'm not kidding, this is true — "Get a Whale of a Deal on a New Oldsmobile."

The explosives expert runs for cover

Umenhofer had received explosives training during his World War II service and what he saw on the beach that day made him very, very nervous. He knew project manager George Thornton was not going to get the results he wanted — he either needed a lot less dynamite, so that the whale would just be pushed out to sea, or a whole lot more, so that it would be torn into tiny pieces. Umenhofer told the Springfield paper he tried to warn Thornton but was blown off.

The explosives non-expert can't wait to push the plunger

Uemenhofer shrugged and made a note to himself to be as far away from the whale as possible when it went off.

"But the guy says, 'Anyway, I'm gonna have everyone on top of those dunes far away,'" Umenhofer told reporter Wayne Freedman of San Francisco TV station KGO in an interview 25 years later. "I says, 'Yeah, I'm gonna be the furtherest SOB down that way!'"

And so he was. But he couldn't know how personally Thornton’s mistake would end up affecting him.

A mighty burst of tomato juice ... the chunky kind

Early Twitter users will remember this image, created for Twitter by

artist Yiying Lu, as the "Fail Whale," which appeared on screen to signify

that Twitter was over capacity.

The story was covered for KATU-2, one of the Portland TV stations, by Paul Linnman, then a fresh-faced young fellow in his mid-20s. As one would expect given his young age, Linnman made a minor error reporting the story — assuming that it was a California Gray whale when it was actually a sperm whale — but in his book he more than makes up for it with one line, which you’ll find on Page 77: “Explosions in the movies usually look like a blast of fire and smoke; this one more resembled a mighty burst of tomato juice.” A mighty burst of tomato juice? Now, that’s painting a picture with words.

If you search for "exploding whale" on Google, you'll find Linnman's story, about two and a half minutes long. You'll see the whole thing, from the guys packing boxes of dynamite to the impressive explosion and the less-impressive aftermath. You'll get to hear George Thornton say -- this is a direct quote -- "Well, I'm confident that it'll work, the only thing is we're not sure how much explosives it'll take to disintigrate this thing ..."

You'll also get to hear the people on the beach watching the blast: yells of excitement turned to disgust, dull thumping sounds, and a woman saying, "OK, Fred, you can take your hands out of your ears now. Here come pieces of —"

You'll also get to see Walt Umenhofer — remember him? The guy who warned Thornton about his plan? Walt appears about two minutes into the video, standing next to his brand-new demolished Oldsmobile. Its passenger compartment had been flattened by a chunk of flying blubber the size of a small truck tire.

What were they thinking?

Linnman’s story was, of course, snatched up by the network and played all over the country. Fifty-year-old retired Army ordinance guys all over the nation, who learned how to blow stuff up during World War II, wondered what the heck Thornton was thinking. Twenty 50-pound cases of dynamite sound like a lot, but in the context of eight tons of untamped, rotting meat, they dwindle to insignificance. And Thornton actually said, on camera, to Linnman, that he wasn’t sure how much dynamite he should be using.

With the benefit of hindsight, it’s pretty easy to wonder why he didn’t pull someone who knew explosives into the project, even if that someone was a know-it-all stranger with a brand-new Olds parked 450 yards away — a stranger like Walt Umenhofer, who got well away from the blast site himself but neglected to collect his car first.

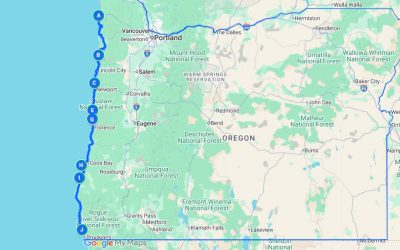

New Car Guy remembers

Umenhofer, who still lives in Springfield, now owns and operates “The Baron’s Den,” a gun store and indoor shooting range just south of Eugene, visible from Interstate 5 (it usually sports a bright blue banner reading "SHOOT A REAL TOMMY GUN"). He tries to avoid talking about the exploding whale, mostly because he’s sick of telling the story.

Humor Columnist Guy gets involved

In any event, the exploding whale — with the help of syndicated humor columnist Dave Barry, who had great fun with it — has become part of our entire nation’s pop culture and has been mistaken for an “urban legend.” Many Florence residents were not pleased — they felt this was the wrong way to get one’s hometown on the map. But today, almost 40 years later, even the crankiest among them chuckle about it — sometimes a bit wistfully.

Dynamite Guy still blames the media

But not George Thornton — who was promoted to the Medford office six months later (a cynical observer might characterize this as being "kicked upstairs"). On the day of the blast, he told reporter Larry Bacon of the Eugene Register-Guard, "It went just exactly right. ... Except the blast funneled a hole in the sand under the whale" (thereby causing some of the whale bits to be blown back toward the parking lot, he went on to say).

Decades later, Thornton was still defiantly sanguine about the whole operation. Contacted by Linnman in the mid-1990s, he refused to be interviewed on camera, and seemed to feel the news coverage of the event had converted a successful exercise into a disaster.

The conversation ended on a sour note when Linnman asked Thornton if he didn't want to tell the public about it — about what had gone wrong that day.

“What do you mean, ‘what went wrong?’” he asked Linnman tersely — apparently by way of implying that nothing had.

(Sources: Linnman, Paul. The Exploding Whale. Portland: West Winds Press, 2003; The Springfield News archives; The Eugene Register-Guard, Nov. 13, 1970)

This story was used with permission, and originally published here at OffBeatOregon.com.