If you’ve been watching HBO’s The Gilded Age, you’ve seen the nation’s transformation play out in gas-lit parlors and drawing-room duels; steel barons and railroad titans building empires as socialites spar over who’s allowed into high society. What the show captures in New York’s ballrooms, Portland, Oregon, lived out on its muddy streets and timber docks.

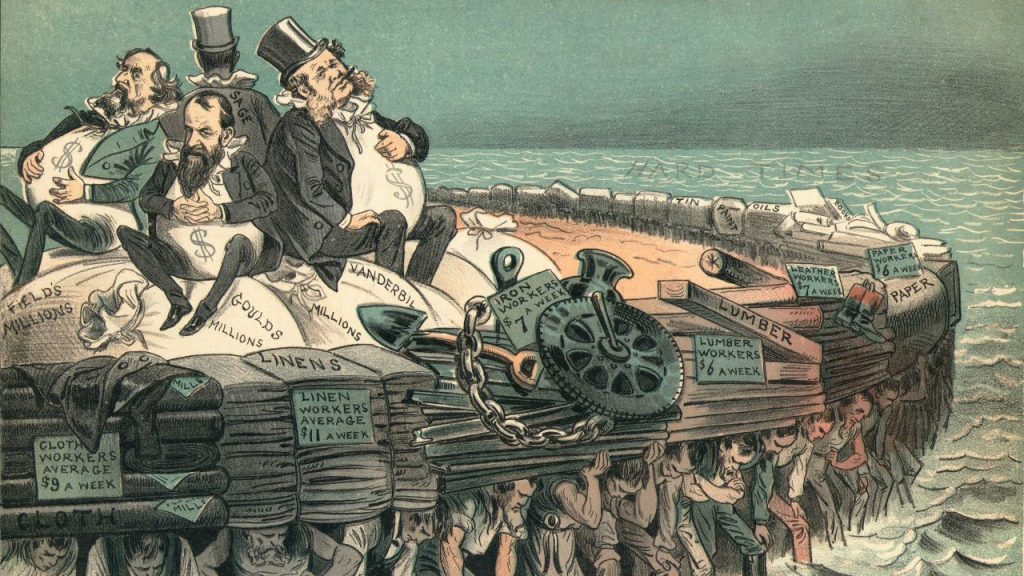

The term "Gilded Age" was coined by Mark Twain to describe the late 19th century in America, a period that appeared prosperous and shiny on the surface but was full of corruption and social unrest beneath. Impure. A thin veneer of golden excess easily worn away.

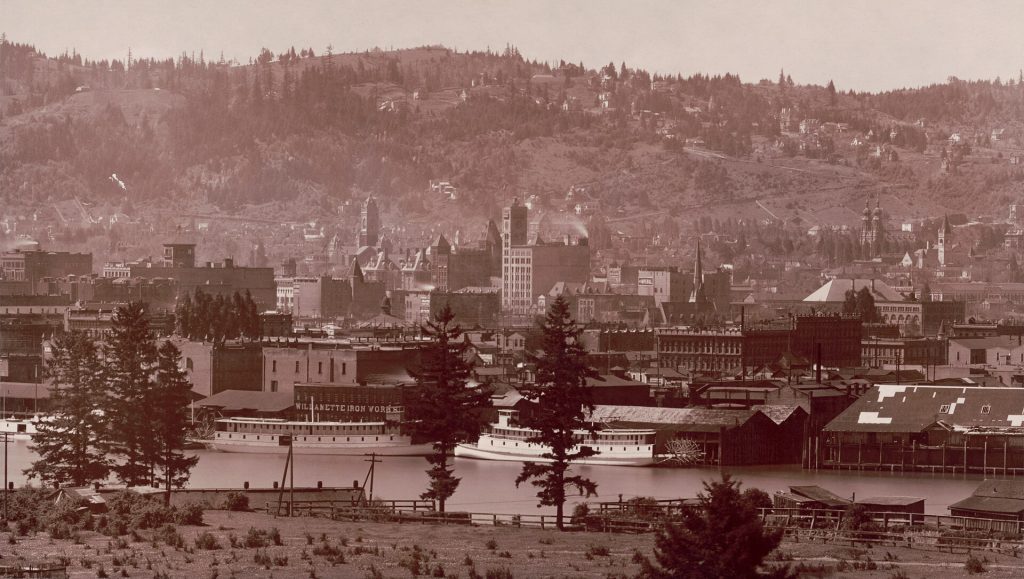

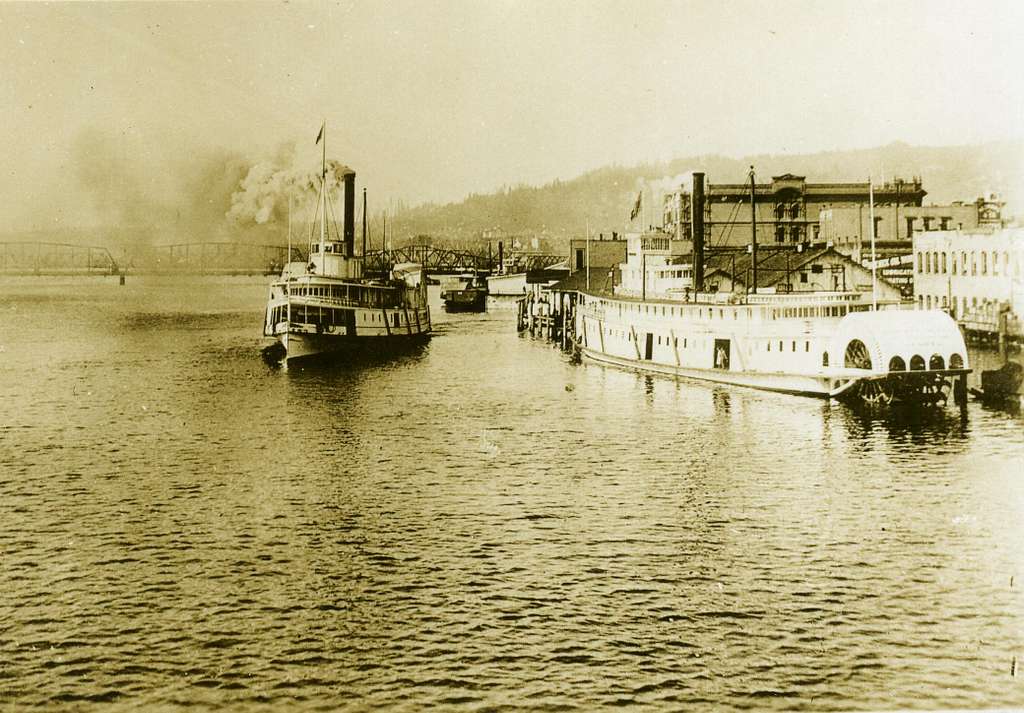

Out here, the Gilded Age wasn’t about silk gowns and chandeliers. It was the hiss of steamships on the Willamette, the clang of rail lines being laid through wilderness, and the glow of brand-new electric lamps pushing back the night. Yet the story was the same: a handful of magnates like Pittock, Ladd, Villard, and Weinhard amassed fortunes from timber, shipping, and railroads while immigrants and laborers built the empire beneath them.

They may never have dined with the Vanderbilts or Astors, but Portland’s tycoons chased the same dream: to tame a frontier and turn it into a kingdom of progress, wealth, and contradiction.

The Port in Flux: Rivers, Steamships, and Trade

By the 1870s, Portland was shaking off its reputation as a muddy frontier town and growing into the Northwest’s commercial heartbeat. The Willamette River was its highway; the Columbia, its open road to the world. Steamships ferried goods downriver while schooners loaded wheat, salmon, and timber for San Francisco and beyond.

The railroad boom brought new momentum. When the Northern Pacific line reached Portland in 1883, Henry Villard’s golden-spike celebration made headlines nationwide. Lumber camps, canneries, and mills funneled their bounty toward the port, where longshoremen shouted over the hiss of steam and the creak of wooden piers. The city smelled of salt, sawdust, and ambition. A frontier outpost rapidly learning to think like a metropolis.

Mansions on the Hill: The Gilded Class Emerges

As trade boomed, Portland’s skyline began to climb. By 1882, maps of the city showed Italianate mansions creeping up the West Hills. Families like the Ladds, Failings, and Pittocks built homes that gleamed with carved woodwork, imported marble, and Tiffany glass.

Henry Pittock, who rose from penniless printer to publisher of The Oregonian, embodied the self-made optimism of the era. His later mansion, complete with elevator, central vacuum, and panoramic views, became a West Coast echo of the Astors’ Fifth Avenue palaces.

For the elite, refinement was both armor and advertisement. They invested in art, opera, and philanthropy, eager to prove that culture could flourish even at the edge of the continent. But beneath the chandeliers, Portland’s prosperity was far rougher than it appeared.

Logging, Railroads, and the Raw Northwest

If New York’s Gilded Age was powered by steel, Portland’s ran on wood. Oregon’s endless forests became the city’s lifeblood. Steam-donkey engines screamed through logging camps, and floating log rafts clogged the rivers.

Railroads cut deep into the Cascades and Coast Range, dragging timber and ore back to mills along the Willamette. The city’s sawdust streets, its wharves, even its homes were built from the wealth of trees that fell by the millions. Every fortune that rose on the West Hills was rooted in the forests beyond them.

Yet the timber boom had its shadows: dangerous labor, ecological ruin, and boom-and-bust volatility. Still, Portland thrived. A city literally built from its surroundings.

Immigrants, Labor, and the City’s Underbelly

Prosperity drew people from everywhere. Chinese immigrants made up more than half of Oregon’s Chinese population by the 1880s, running laundries, shops, and restaurants in the heart of Portland’s Chinatown. Scandinavian and Irish workers loaded ships and laid track.

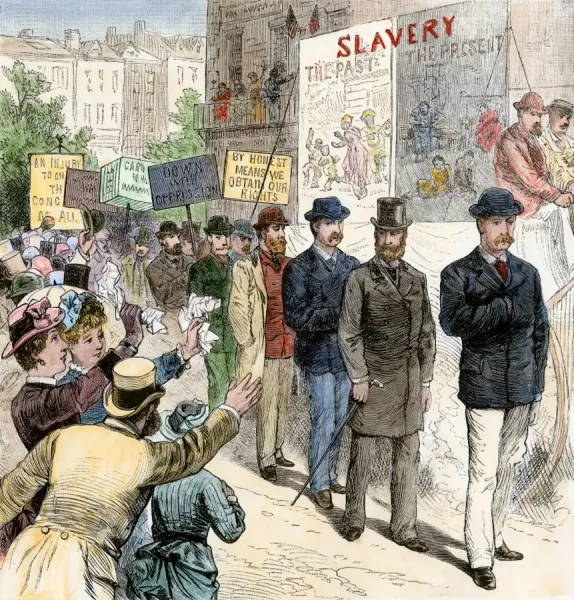

But racism and exploitation haunted the era. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 froze immigration, while violent mobs terrorized workers. In the alleys beneath the city, the now-famous Shanghai Tunnels whispered stories of men kidnapped and sold to sea captains, a blend of truth and legend that captured the darker side of the boom.

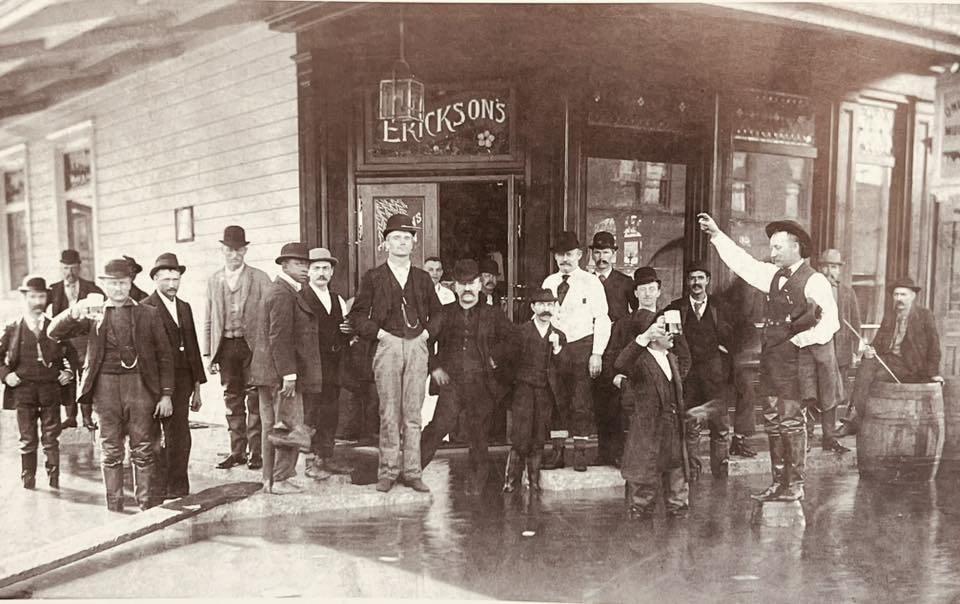

Vice thrived in Old Town’s narrow streets: gambling dens, opium houses, and saloons outnumbered churches. Wealthy Portlanders attended civic galas by night while the working poor filled flophouses by the river.

Vice and Respectability: Two Sides of the Same Coin

Portland’s Gilded Age was an odd marriage of refinement and revelry. The same year the grand Portland Hotel opened its marble-lined doors, Erickson’s Saloon served beer by the gallon in a 684-foot barroom that stretched nearly a city block.

Moral crusaders railed against vice, but the city’s economy depended on it. The docks ran on liquor, gambling kept cash moving, and opium dens serviced exhausted sailors. When civic leaders dedicated Skidmore Fountain in 1888 as a gift to “the people”, Henry Weinhard offered to pump beer through its pipes. It was refused, but Portland loved him for asking.

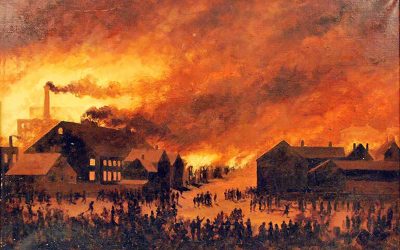

Shaping the City: Fire, Rebuilding, and Electric Dreams

On August 2, 1873, a catastrophic fire swept through downtown, leveling 22 blocks of the city, including two Engine Houses, two sash factories, three foundries, four mills, five hotels, 100 retail stores, and 250 dwellings. Instead of ruin, however, Portland saw rebirth. Brick and cast-iron architecture replaced timber. The skyline hardened into permanence.

By the 1890s, the city buzzed with innovation. George Weidler’s Willamette Falls Electric Company sent power 13 miles from Oregon City: the world’s first long-distance transmission of electricity. Streetcars rattled up the hills. Telephones linked homes and businesses. The Oregonian Building rose as the West’s first steel-frame high-rise, its clock tower marking a new century of ambition.

Yet amid the progress, inequality deepened. Sanitation lagged, tenements grew crowded, and labor unrest flared. The bright lights illuminated both triumph and turmoil.

The Undercurrent of Reform

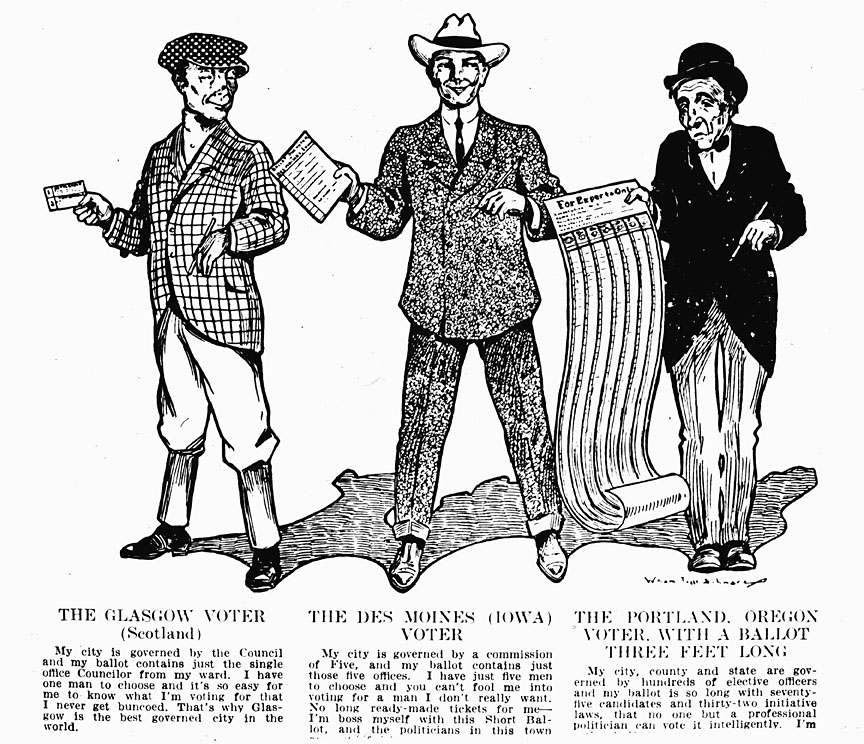

By 1900, the cracks in Portland’s golden veneer were visible. The Panic of 1893 humbled its financiers, and reformers, many of them women, began demanding cleaner government, safer workplaces, and fairer pay.

Labor movements gained ground. Progressive reformers pushed for civic improvements: better housing, sanitation, child-labor laws, and public schooling. The remnants of the Gilded Age glimmered in mansions and shipping logs, but the dark side was awakening to public view.

Moreover, the city’s character was set. That tension between the independent, frontier-spirit West and the East Coast-refined Gilded Class would shape Portland’s identity for decades. The physical infrastructure built during this era: mills, mansions, docks, and railroads left their mark.

Progressives organized unions, suffrage campaigns, and anti-corruption leagues. Churches opened soup kitchens. Newspapers (including Pittock’s Oregonian) debated the ethics of wealth. Portland was growing up uneasy, defiant, and self-aware.

The Barons of the Pacific Northwest

Portland’s rise mirrored that of the Eastern elite, only on a smaller, scrappier scale. Henry Villard was the city’s Vanderbilt, chasing railroads instead of steamships. Henry Pittock was its Carnegie, building an empire from paper and principle. William Ladd ruled finance like Rockefeller, quietly controlling the city’s purse strings. Henry Weinhard brewed prosperity with Astor’s flair, and George Weidler electrified it all like a frontier J.P. Morgan.

Together they transformed a muddy port into a regional powerhouse, a “Gilded Age in miniature” that shimmered with the same paradoxes as New York or Pittsburgh: progress born of exploitation, charity mixed with self-interest, grandeur shadowed by grit.

Henry Villard: The Railroad Dreamer Who Built Portland’s Future

When Henry Villard came west, he brought with him a vision big enough to rival any titan of the East. A German immigrant who began as a journalist covering the Civil War, Villard pivoted into finance and soon controlled the Oregon & California Railroad, the Oregon Railway & Navigation Company, and finally the Northern Pacific Railway. By 1883, Portland pulsed with anticipation as Villard’s transcontinental rail link neared completion. His “Golden Spike” celebration that year drew governors, industrialists, and reporters from across the country.

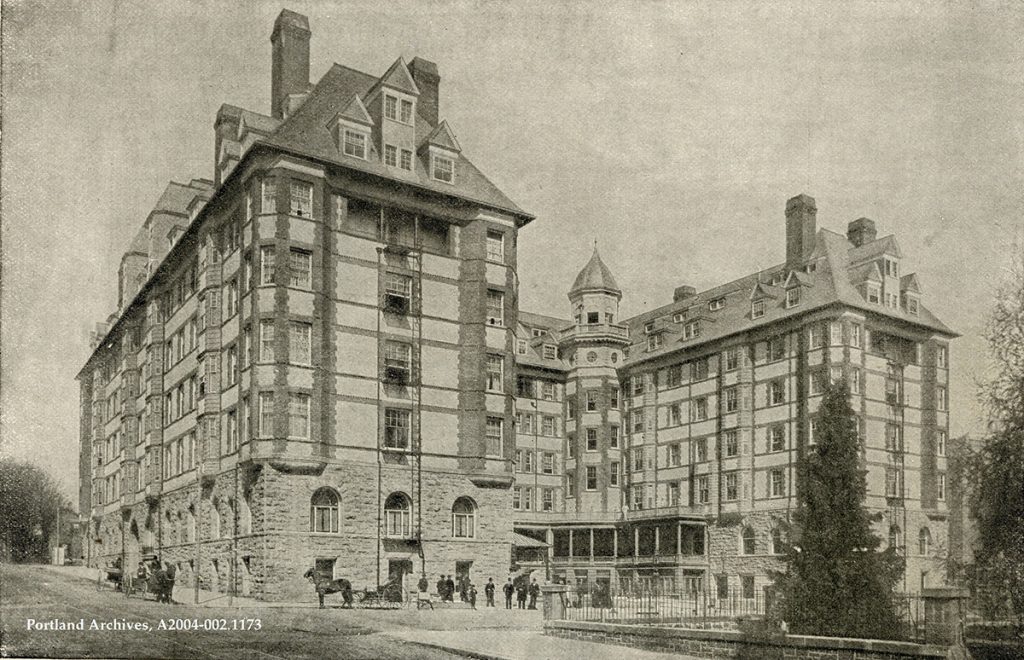

Villard saw Portland not as a remote outpost but as the future gateway of the Pacific Northwest. A San Francisco in waiting. He poured millions into infrastructure: telegraph lines, shipping docks, and the grand Portland Hotel, an eight-story European-style showpiece meant to crown the city’s civic pride. Yet the same year the rails met, his empire buckled under debt. Bankers back East ousted him, his fortune collapsed, and the hotel sat half-finished. Villard’s fall was swift, but his ambition permanently altered Oregon’s destiny. Every locomotive echoing through Union Station still hums with his name.

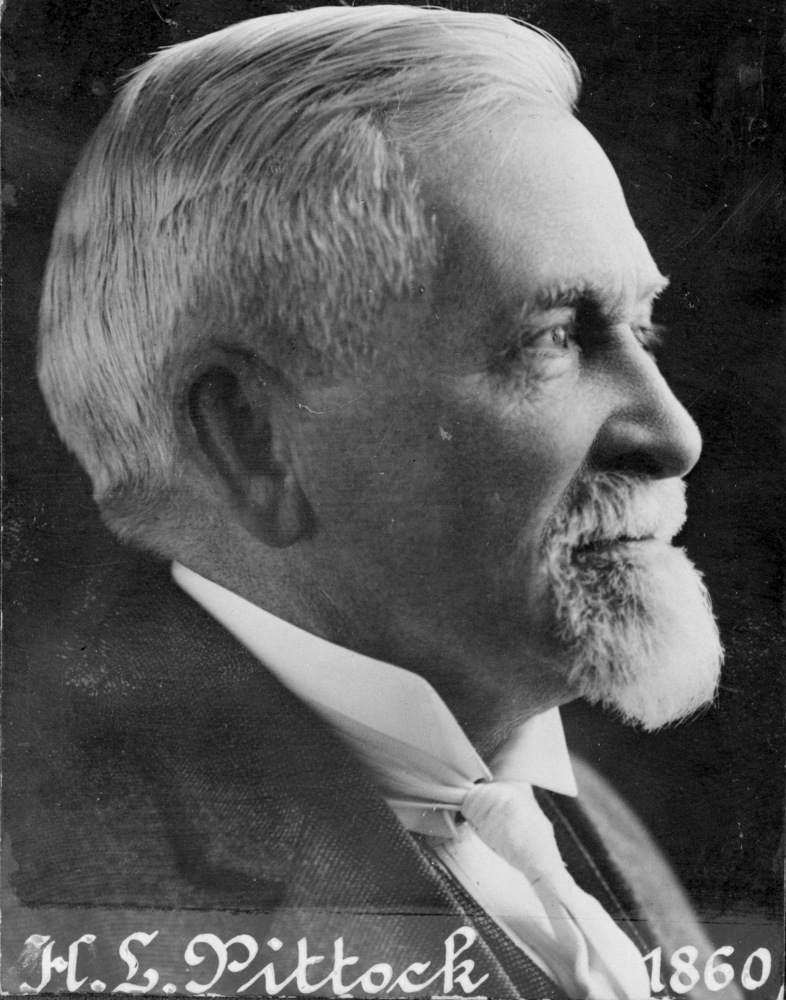

Henry L. Pittock: The Publisher Who Built an Empire on Paper and Ambition

Few men embodied Portland’s self-made spirit like Henry Pittock. Born poor in London and raised in Pennsylvania, he arrived in Portland at the tender age of 19 to work as a typesetter for The Oregonian. When the paper’s owner defaulted on wages in 1860, Pittock took the struggling daily as payment and turned it into Oregon’s voice of record. He modernized printing, built his own pulp and paper mills, and used the profits to expand into real estate, logging, and transportation.

By the 1890s, Pittock’s influence reached every corner of the city. His name graced streetcar companies and civic boards. His editorials shaped politics, yet he never lost the craftsman’s curiosity that drove him from the pressroom. His hilltop home, Pittock Mansion, completed in 1914, symbolized more than wealth. It was a showcase of technology and taste, featuring telephones, central vacuum systems, and panoramic views of the empire he’d helped build.

Like Carnegie, whom he resembled in both ambition and philanthropy, Pittock believed industry could civilize the frontier. The Oregonian he built still prints his motto: “Everywhere the Press, Everywhere Progress.”

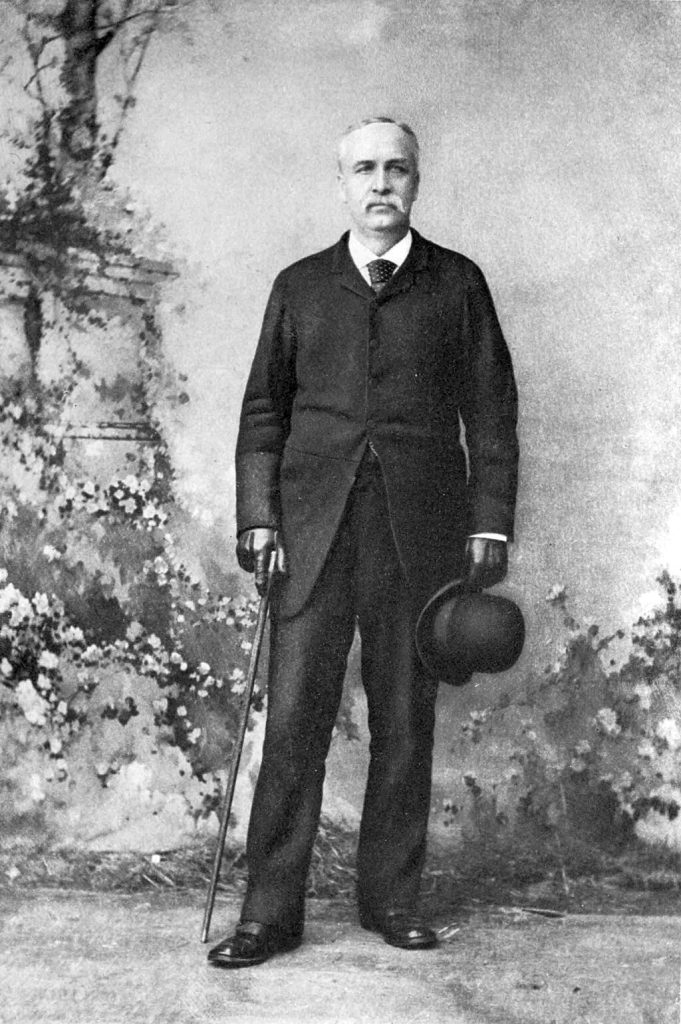

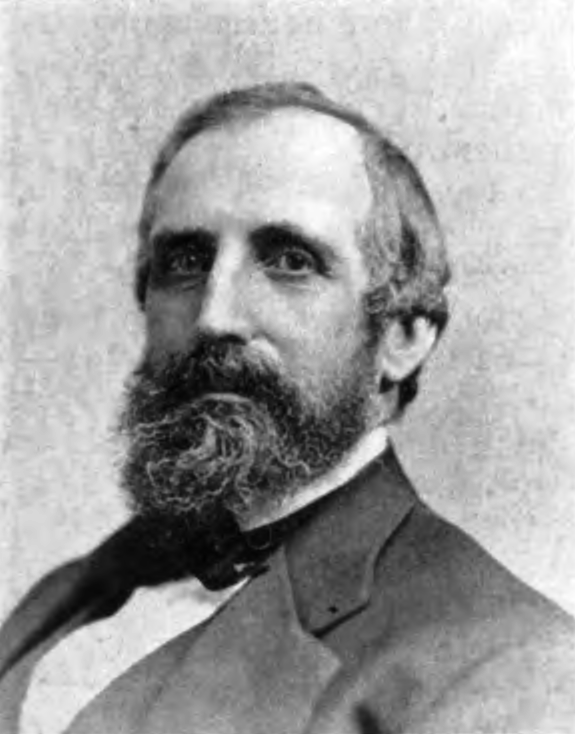

William S. Ladd: The Banker Who Quietly Owned the City

In a city of dreamers and drifters, William Sargent Ladd was the steady hand that kept the money flowing. A Vermont native who arrived by ship in 1851, he quickly grasped that Portland’s muddy streets hid golden potential. In 1859, with a single-room office and a safe bolted to the floor, he founded Ladd & Tilton Bank, the first north of San Francisco.

Through loans and investments, Ladd financed railroads, mills, and warehouses that transformed Portland into the Northwest’s commercial hub. His quiet demeanor belied immense influence: two-time mayor, philanthropist, and architect of the city’s first credit system. By the 1880s, nearly every major enterprise, from steamboats to breweries, depended on his capital.

Ladd’s wealth flowed into land: he bought vast tracts that became Ladd’s Addition and the West Hills estates. His cautious, calculating style echoed Rockefeller’s: control the flow of capital, and you control the future. Yet Ladd’s generosity softened his reputation; he donated to hospitals, churches, and schools. When he died in 1893, Portland paused. The banker who built its bones had become its conscience, too.

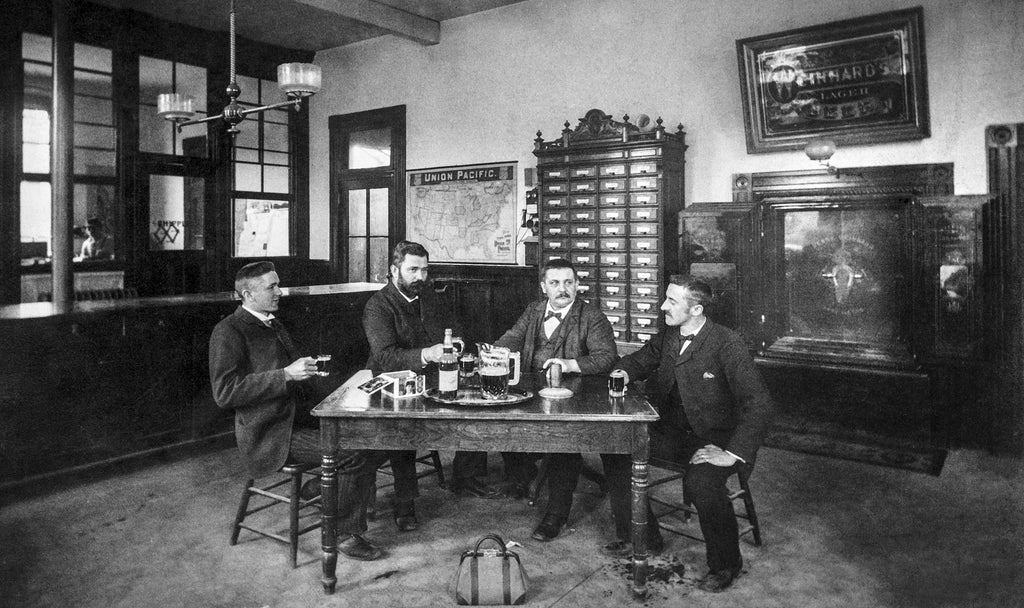

Henry Weinhard: The Brewer Who Bottled the Spirit of Portland

Long before Portland crowned itself “Beervana,” Henry Weinhard was already pouring its legend. A German cooper turned brewer, he arrived in Oregon in the 1850s and founded City Brewery, which by the 1880s was the largest on the Pacific Coast. His lagers quenched loggers, merchants, and miners alike, liquid gold in a city that still smelled of sawdust and ambition.

Weinhard’s success story was classic immigrant grit. He modernized production, introduced pasteurization, and built a bottling empire that reached California and beyond. For Portland’s 1888 unveiling of Skidmore Fountain, he famously offered to pump beer through the water pipes, a publicity stunt so audacious it became local folklore.

Beneath the humor was a shrewd businessman with Astor-like instincts for branding and real estate. He bought downtown property, funded charities, and turned his brewery complex into an industrial landmark.

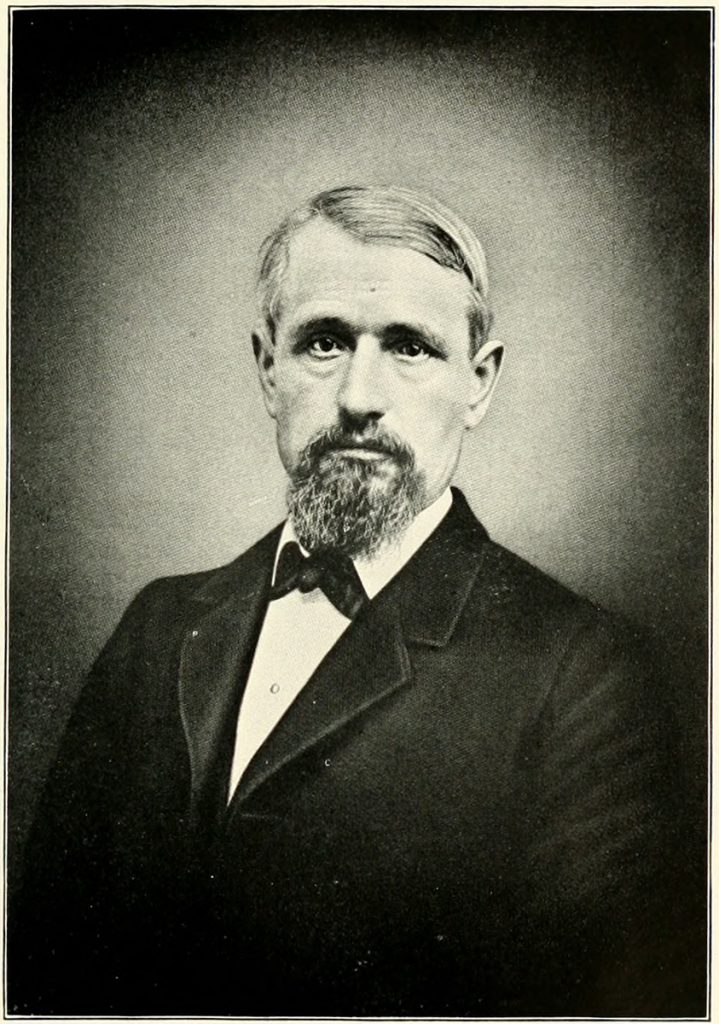

George W. Weidler: The Electric Visionary Who Lit the West

George Washington Weidler rarely made headlines, but his fingerprints are on Portland’s first glow of modern light. A former lumberman turned entrepreneur, Weidler saw promise not just in wood and steam, but in invisible power: electricity. In 1889, his Willamette Falls Electric Company achieved a world first: transmitting electric current 13 miles from Oregon City to downtown Portland. It was a quiet revolution, pre-dating even Edison’s large-scale systems back east.

Weidler’s interests spanned shipping, utilities, and telecommunications. He co-founded the Oregon Telegraph Company and invested heavily in Portland’s streetcar and lighting infrastructure. Like J.P. Morgan, he understood that whoever financed the grid controlled the future. His operations connected mills, factories, and homes in ways the average citizen barely comprehended, yet everyone felt his influence when the lamps flickered to life.

When Union Station opened in 1896, its electric clock tower symbolized that new age. Behind that light, somewhere in the quiet offices of Weidler’s enterprises, the power broker of Portland’s Gilded Age smiled, content to illuminate a city, even if few knew his name.

Why Portland’s Early Steel-Frame and Cast-Iron Buildings Were Torn Down

Portland’s first skyline was born in the Gilded Age: steel-frame towers, cast-iron storefronts, and ornate hotels that glittered above muddy streets. But by the mid-20th century, the same buildings that once symbolized progress were seen as relics.

In the 1950s and ’60s, “urban renewal” swept through Portland like a second gold rush, this time for modernity. The old cast-iron blocks along Front Avenue and the ornate Portland Hotel were razed to make way for glass towers, freeways, and parking lots. Even the Oregonian Building, the West Coast’s first steel-frame skyscraper, fell to demolition crews in the early 1950s.

City leaders called it modernization. Preservationists later called it erasure. Fires, lax building codes, and changing tastes made restoration seem impractical, and entire neighborhoods were bulldozed under the promise of cleaner, brighter futures.

By the time Portland realized what it had lost, the craftsmanship, the texture, the living link to its Gilded Age, much of it was gone.

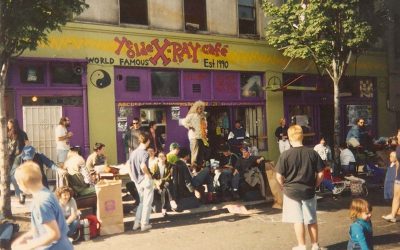

The backlash to that destruction birthed Portland’s preservation movement. In the 1970s, activists fought to save the Skidmore/Old Town Historic District, now a protected window into the 19th century. The rest exists only in photographs: gilded facades, vanished towers, and a skyline that forgot its own reflection.

A Gilded Age Legacy: Portland Then and Now

Stroll through Portland today and traces of that age remain. The Pittock Mansion still surveys the city from its perch in the hills. Skidmore/Old Town’s cast-iron facades recall a time when the waterfront was the city’s lifeline. Union Station’s clocktower still watches over the skyline.

Every era since, from the civic reformers of the 1910s to the counterculture of the 1970s, has wrestled with the same contradictions first forged in the Gilded Age: wealth and want, innovation and inequity, high ideals and human vice.

A century and a half later, Portland still struggles with the same tensions that defined its first boom. Then, it was timber and trade. Today, it’s tech and tourism. Then, opulent mansions rose above muddy streets. Now, luxury condos overlook tents pitched in the rain. The faces and fortunes have changed, but the rhythm feels hauntingly familiar.

The Gilded Age promised progress for all but delivered prosperity for a few, a dynamic Portland still knows well. The same city once electrified by George Weidler now debates how to power its future sustainably. The paper empire that made Henry Pittock rich has given way to a digital one built on clicks, code, and speculation. And as in 1890, Portland’s biggest questions aren’t about wealth itself, but about who benefits when the city booms.

“Every generation in Portland builds its own version of the Gilded Age: new industries, new ideals, same fragile balance between progress and people.”

Look closely and you can still see it: the shimmer and the shadow. A skyline of cranes where sawmills once stood. Breweries in the bones of old warehouses. The glow of streetlights reflecting off wet pavement is a reminder that history doesn’t end; it reinvents itself. Portland has always been a city of builders, dreamers, and barons. The only difference now is what we choose to gild.

Just as HBO’s The Gilded Age reveals the moral tension beneath the velvet, Portland’s own story reminds us that prosperity always comes at a price, and that history, like the Willamette, keeps rolling forward, carrying the shimmer and shadow of those who built its banks.