If you live in the Pacific Northwest there's a good likelihood that the land you're standing on is part of a massive floodplain; silt, and rock deposits swept here from Montana during the end of the last Ice Age. The floods advanced with a vengeance, unstoppable and vast in a matter of DAYS, not months.

The Missoula Floods

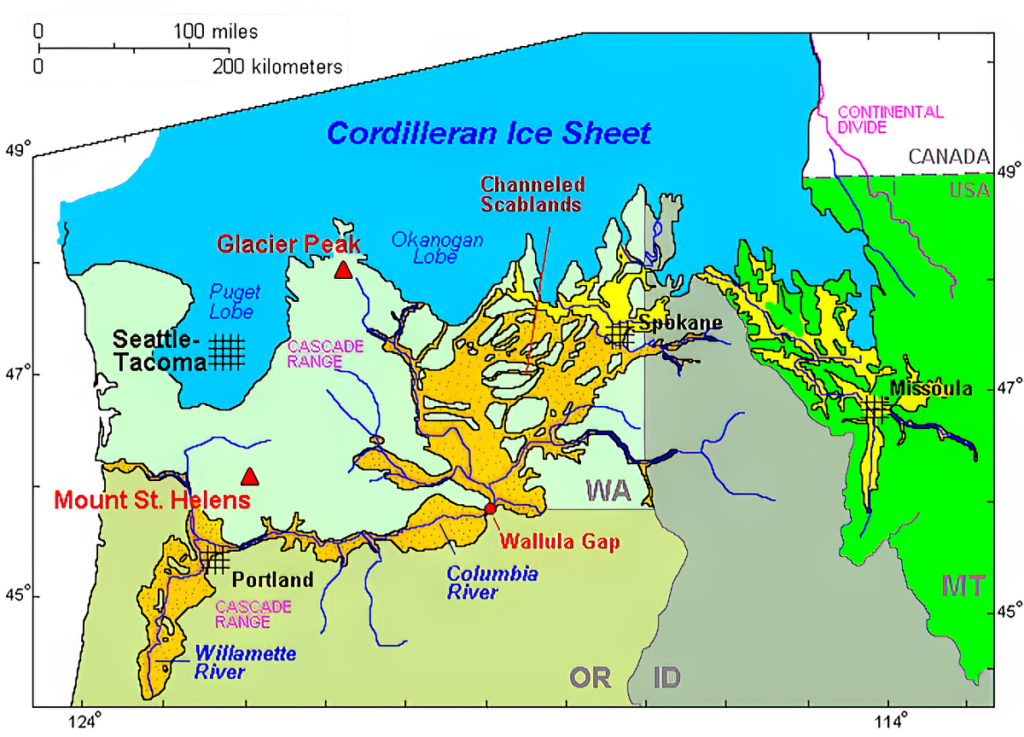

The Missoula Floods, a series of cataclysmic events during the last Ice Age, profoundly shaped the Pacific Northwest, including the landscape of Oregon that we're so familiar with today. When the massive Cordilleran ice sheet advanced into Montana and Idaho, it dammed the Clark Fork River, forming Glacial Lake Missoula, a body of water comparable in size to today's Lakes Ontario and Erie combined. The only barrier holding back this immense lake was a 2000-foot-high ice dam, which periodically failed, unleashing catastrophic floods that surged across the region at speeds of up to eighty miles per hour.

The floods unleashed a staggering 1.9×10¹⁹ joules of energy with each event. To put that into perspective, this energy release was equivalent to 4,500 megatons of TNT, making each flood 90 times more powerful than the most powerful nuclear weapon ever detonated, the 50-megaton "Tsar Bomba."

U.S. Geological Survey hydrologist Jim O'Connor and Spain's Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales scientist Gerardo Benito have found evidence of at least twenty-five of these massive floods, the largest discharging water, icebergs, silt, and boulders at about 10 cubic kilometers per hour, equivalent to 13 times the volume of the Amazon River.

The Floods Were Essentially The First "Oregon Trail"

The water from Glacial Lake Missoula flowed westward, joining with other glacial lakes like Lake Columbia, and carved its way through the landscape. As these floods raged, they scoured vast areas of eastern Washington, leaving behind the Channeled Scablands, a barren landscape stripped down to the basalt bedrock. The floods also shaped the Columbia River Gorge, creating the deep channels and dramatic waterfalls we see today.

One of the most remarkable impacts of these floods is seen in Oregon’s Willamette Valley. Floodwaters, laden with rich silt and debris, periodically diverted south into the valley, leaving behind incredibly fertile soil deposits up to 300 feet deep in some areas. This nutrient-rich earth stretched as far south as Eugene, transforming the valley into a prime agricultural region.

However, while the Willamette Valley benefited from these floods, other regions were less fortunate. Eastern Washington, in particular, was left with vast tracts of bare rock, a testament to the destructive power of the floods. The Missoula Floods didn’t just move soil; they also transported enormous boulders, known as glacial erratics, across great distances, leaving a geological record of their force.

These floods, occurring between 19,000 and 13,000 years ago, with evidence suggesting even earlier occurrences, were a defining force in shaping the Pacific Northwest. The legacy of these events is etched into the region’s landscape, from the fertile soils of the Willamette Valley to the rugged Scablands of eastern Washington.

Side note: If you're interested in the actual Oregon Trail, we highly recommend checking out our Ultimate Oregon Trail Road Trip guide.

Where Can You See Evidence of the Missoula Floods Today?

If you live in the US States of Montana, Idaho, Washington, and Oregon, the evidence is all around you if you know where to look. The Ice Age Floods Institute created a handy, interactive map for those interested in the ancient geologic history of the Pacific Northwest. Some of our favorite sites include the following.

Central Washington State

With too many incredible geological features to mention, Washington's Missoula Flood evidence is vast and awe-inspiring.

Last summer, I took a four-day road trip into the region of Hanford Reach National Monument and up into the scablands of the Columbia Plateau. Amidst rural farmland and wine country lie massive coulees, gravel fields, giant erratic boulders, and sweeping geologic formations as a testament to the floods.

Some of the most captivating are White Bluffs Scenic Area, Drumheller Channels National Natural Landmark, West Bar, Moses Coulee, Dry Falls, Palouse Falls, and the Ephrata Fan.

Rowena Crest, Mosier, Oregon

Rowena Viewpoint is mostly known as a wonderful wildflower-viewing area and picnic spot, with sweeping views of the Columbia River Gorge, but its ancient history is interwoven with the Missoula Floods.

This rocky promontory stood directly in the path of floodwaters thundering through Rowena Gap to the east. As the waters crashed over and around this point, they sculpted kolk ponds, mysterious Mima mounds, and oversized canyons, while also undercutting the cliffs and causing massive landslides. The town of Lyle, WA, across the river, sits atop a massive eddy bar that once temporarily blocked the mouth of the Klickitat River.

The Rowena Crest promontory played a crucial role in creating a chokepoint that led to the formation of terminal Lake Condon within the Dalles basin. This lake backed up all the way to the downstream end of Wallula Gap, while terminal Lake Lewis formed on the upstream side.

Columbia Gorge Discovery Center & Museum, The Dalles

The Kolk pond behind the Columbia Gorge Discovery Center was carved from basalt bedrock by powerful whirlpools that formed in this turbulent zone, where the floodwaters surged through Rowena Gap after pooling in the transient lake of The Dalles basin. You can also spot faint turbulence-cut benches on the hillsides north of the Columbia River.

The Discovery Center’s natural history museum features several exhibits related to the Missoula Floods, making it a fascinating visit for those interested in the region's geological history.

Beacon Rock

As the Ice Age floods thundered through the Columbia River Gorge, they stripped away the volcanic cinder cone that once surrounded the basalt core of a minor Pliocene volcano, leaving behind the prominent Beacon Rock. This 848-foot basalt monolith, once the heart of a volcano, stands on the north bank of the Columbia River and is one of the tallest monoliths in North America, comparable to El Capitan and Devils Tower.

Native Americans called it "Che-Che-op-tin," meaning "the navel of the world," reflecting its significance. Beacon Rock has a rich history—Lewis and Clark camped here in 1805 and noted the ocean tides affecting the Columbia River’s water levels over 120 miles from the coast.

The rock's iconic mile-long switchback trail, offering stunning views of the Columbia River Gorge, was built between 1915 and 1918 by Charles Johnson and Henry Biddle, who saved the rock from demolition. Though initially rejected by Washington State Parks, Beacon Rock eventually became part of a 4,650-acre state park after Oregon expressed interest in maintaining it. The park now features nearly two miles of freshwater shoreline along the Columbia River.

Crown Point - Vista House

Vista House at Crown Point offers a breathtaking view of the floodwaters’ exit from the Gorge, along with the gravel bars left behind as the water slowed upon entering the Portland basin. While it’s famously dubbed the most expensive restroom in the country, Vista House is also one of the crowning jewels of the Historic Columbia River Highway.

Mocks Crest to Overlook Park, Portland

Mocks Crest to Overlook Park features a steep 300-foot slope on the west side of the Overlook neighborhood, descending to near river level. The Waud Bluff Trail from Mocks Crest guides you down 140 feet through gravels and cobbles deposited by the Missoula Floods during the last Ice Age.

Fields Bridge Park and Willamette Meteorite, West Linn

Fields Bridge Park in West Linn, OR, offers a 0.2-mile nature walk along the Tualatin River, featuring three kiosks and eight interpretive panels that share the story of the Ice Age Floods. This scenic trail is located just two miles from the discovery site of the Willamette Meteorite, the largest meteorite found in the United States and the sixth largest in the world.

The Willamette Meteorite, believed to have originated in northern Idaho, Montana, or just across the Canadian border, was carried over 400 miles to its final resting place in the Willamette area by the Ice Age Megafloods. After being displayed at the 1902 Lewis & Clark Exposition, it was donated to the American Museum of Natural History in New York, where it now resides in the Hayden Planetarium.

Willamette Falls, Oregon City

Willamette Falls, the second largest waterfall in the United States by volume, was formed as a receding waterfall during the Ice Age Floods, dropping 50 feet on the Willamette River. Designated a National Heritage Area in April 2015, this falls has long been a significant historic, cultural, and industrial site. It served as a vital trading and fishing spot for Native Americans, marked the end of the Oregon Trail for pioneers, and in 1889, witnessed the first long-distance transmission of electrical power.

Above Willamette Falls, the scablands, eroded by the Ice Age Floods, include Camassia Nature Preserve in West Linn and Canemah Bluff Nature Park in Oregon City. These areas offer nature walks where visitors can explore the unique ecology shaped by these ancient events.

Be inspired as you view the falls, imagining Ice Age Floodwaters towering several dozen feet overhead, carving and shaping the falls as they receded.

Erratic Rock State Natural Site: The Bellevue Erratic

Six miles west of McMinnville, off Highway 18, sits the Bellevue Erratic, a 90-ton rock that was carried nearly 500 miles in an iceberg during the Ice Age Floods. Originally from the Northern Rocky Mountains, this massive boulder is the largest iceberg erratic found in the Willamette Valley. When the iceberg encasing it melted, the rock was deposited at an elevation of 300 feet. Visitors can take a short uphill hike to the Erratic Rock State Natural Site, where they can view the landscape and imagine the vast floodwaters that once filled the valley.

This boulder, made of banded argillite, can be traced back over 400 miles to the 1.5 billion-year-old Belt Supergroup beneath Glacial Lake Missoula in northern Idaho, the source of the distinctive pinkish Missoula flood sediments.

The presence of erratic rocks at or below the 400-foot elevation in the Willamette Valley reveals that the floodwaters once inundated the region from Portland to Eugene, reaching up to 400 feet above today's sea level.