Today marks 45 years since the catastrophic eruption of Mount St. Helens, a day etched into the history of the Pacific Northwest—and the minds of everyone who lived through it. On the morning of May 18, 1980, at 8:32 a.m., the mountain violently exploded, forever reshaping the landscape of southwest Washington and altering the way America understood volcanoes. Among the lives lost that day was USGS geologist David Johnston, who had been monitoring the volcano from the Coldwater II observation post. His final radio message—“Vancouver! Vancouver! This is it!”—became one of the most haunting legacies of that tragic morning.

The blast was unlike anything ever seen in the continental U.S. A magnitude 5.1 earthquake triggered the largest landslide in recorded history, uncorking the volcano’s north flank and unleashing a lateral blast that scorched everything in its path. The ash cloud rose 15 miles into the sky, and pyroclastic flows devastated 230 square miles of forest. Entire ridges were flattened. Trees were snapped like matchsticks. Ash rained down as far away as Oklahoma.

Fifty-seven people died that day, caught by the fury of a mountain most didn’t believe could explode so violently.

Among those lost was a man who, even decades later, remains a symbol of rugged independence—and tragic stubbornness.

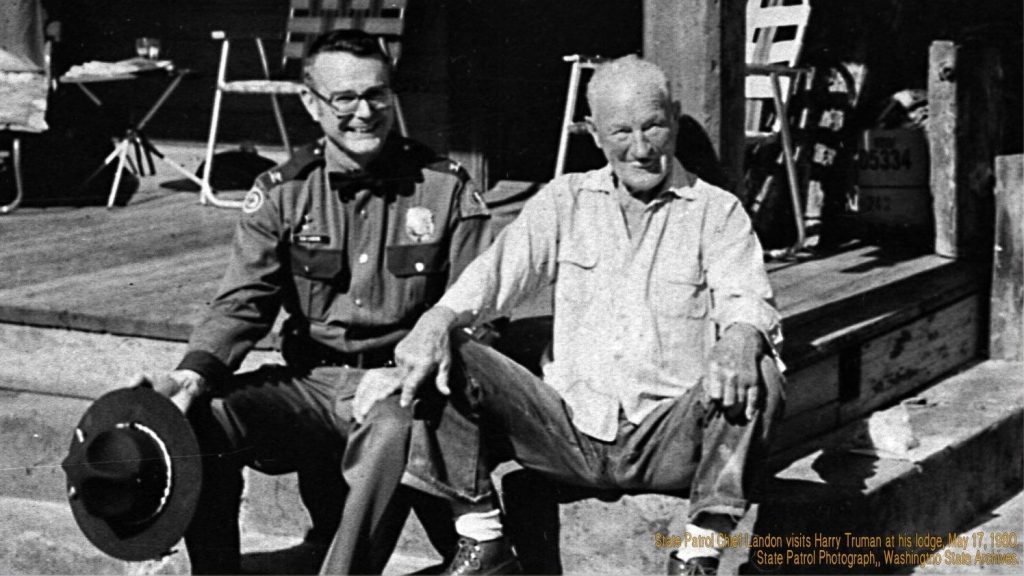

The Man Who Wouldn’t Leave: Harry R. Truman

Not to be confused with the former president, Harry Randall Truman was the 83-year-old owner of the Mount St. Helens Lodge at Spirit Lake. In the weeks leading up to the eruption, geologists warned of a likely catastrophe. Swarms of earthquakes. Rising magma. Visible bulging on the mountain’s north side.

But Truman wasn’t buying it.

"I don’t have any idea whether it will blow," he famously told reporters. "But I don’t believe it to the point that I’m going to pack up."

Harry became a folk hero of sorts. Grumpy, colorful, and completely unbothered by the scientists, he stayed put with his 16 cats, giving interviews and sipping whiskey from the porch of his lakeside lodge—just a few miles from the volcano’s summit.

On May 18, 1980, when the mountain finally blew, Harry Truman and his cats were buried beneath hundreds of feet of volcanic debris. Spirit Lake was blasted out of its basin and repositioned. The lodge was vaporized.

No trace of him was ever found. You can listen to the last known interview with Harry Truman, the man who famously refused to evacuate Mount St. Helens, at this link on Lars Larson’s website.

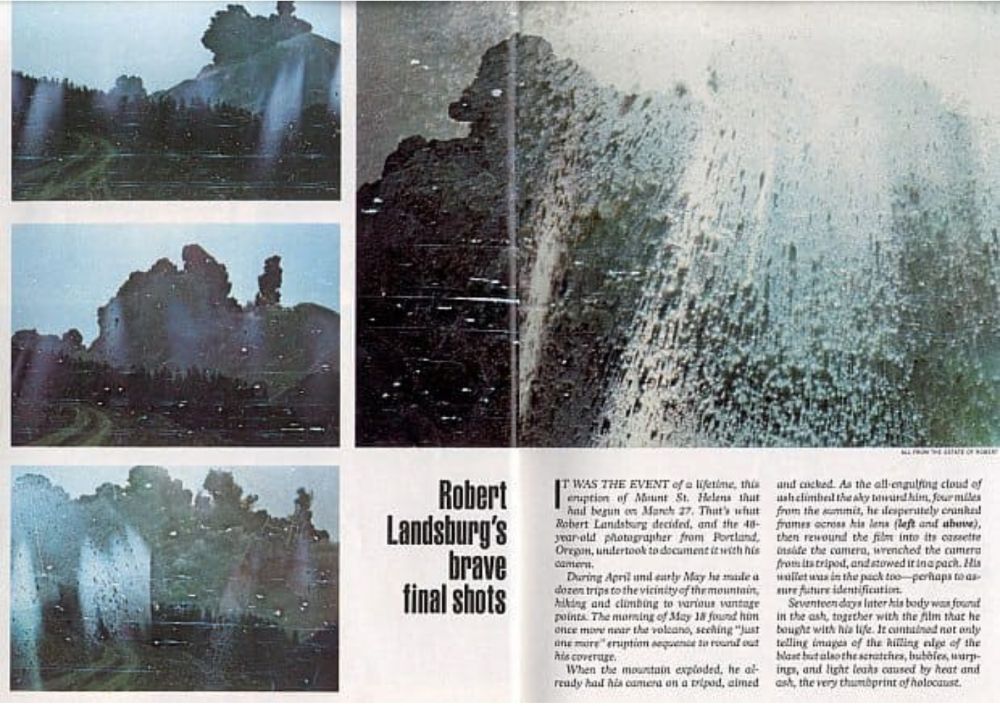

Robert Landsburg, a 48-year-old freelance photographer from Portland, Oregon, was among the 57 victims of the catastrophic Mount St. Helens eruption on May 18, 1980. Positioned just four miles west of the volcano, Landsburg captured a series of photographs documenting the eruption's onset. As the pyroclastic flow rapidly approached, he rewound the film into its canister, placed it in his backpack, and shielded it with his body. Seventeen days later, his body was discovered, and the preserved film provided invaluable visual documentation of the eruption's initial moments.

A Changed World

Mount St. Helens didn’t just take lives—it reshaped science. It became a case study in volcanology, prompting sweeping changes in how the U.S. monitors active volcanoes. It also changed local economies, ecosystems, and tourism. Today, the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument stands as a testament to nature’s power and the resilience of life. Forests are returning. Wildlife has rebounded. But the scars are still visible.

And every May 18, people stop to remember that morning in 1980, when the sky went dark and a mountain taught the world just how alive it still was.

On this 45th anniversary, we remember those who lost their lives—not just Harry Truman, but loggers, scientists, campers, and pilots—caught by an eruption that few could have truly imagined. We honor the power of the natural world, and the lessons learned when we fail to respect it.

As the mountain sleeps, we keep watching. Because as history has shown, it only takes one morning to change everything.

📍 Plan a visit to the Mount St. Helens Visitor Center to learn more about the eruption, the science, and the legacy left behind. Nature may heal—but it never forgets.