The Flat Fire, which has already burned 23,000 acres of forestland and destroyed multiple homes near Sisters, Oregon, has become more than a natural disaster. It is now the subject of a fierce debate about truth, responsibility, and the human role in wildfires that devastate Central Oregon each summer. At the center of that debate is independent journalist Kevin Dahlgren, whose reporting on the ground has sparked heated conversations about whether homeless encampments are being unfairly blamed or carefully protected by political narratives.

Dahlgren, known for documenting homelessness across Oregon on his social media platforms, was among the first to bring public attention to what he described as the likely origin site of the Flat Fire. In a detailed report on his website, he pointed to a sprawling encampment consisting of more than a dozen RVs, tents, makeshift shacks made from scrap wood, shipping containers, abandoned cars, newer cars without license plates, and even old boats. The site, he wrote, had no plumbing or electricity, just mountains of trash and the trappings of long-term habitation. Dahlgren described it plainly as a homeless or squatter encampment.

He published first-hand accounts including that of homeowner Holly Siebert, who lived closest to the reported ignition point and was the one who called 911. Siebert’s account painted a picture of a family devastated not only by fire but by years of frustration with the occupation of nearby lands. She told Dahlgren that she lost over 100 acres of her property, a catastrophic blow to her livelihood and property value. Siebert recalled stories of squatters openly moving between the encampment and local stores, at times intoxicated and shoeless, and expressed her fear that even after the fire these individuals could return. She pleaded for elected officials to recognize that allowing homeless settlements on both public and private lands was creating an ongoing threat to the safety of entire communities.

Dahlgren’s reporting also noted that this is not an isolated warning. Two years ago, local leaders met with Senator Ron Wyden in the Deschutes woods to raise alarm about the risk of man-made fires, only to have those concerns brushed aside in favor of broader discussions about climate change. In his piece, Dahlgren argued that political deflection has left Oregon vulnerable to precisely the kind of disaster that unfolded this summer.

As his reporting spread across social media, where Dahlgren commands more than 67,000 followers, the story quickly fed into a larger narrative. To many, his description of the encampment matched what locals had long feared: that unregulated habitation in Oregon’s forests would one day spark a blaze capable of swallowing towns. For others, Dahlgren’s work was a dangerous attempt to scapegoat the homeless. The controversy reached new levels once elected officials weighed in.

The Bend Bulletin published its own article days later, offering a very different account. At a Deschutes County Commission meeting, Commissioner Phil Chang opened by insisting that the Flat Fire did not start in a homeless encampment. Chang said he was speaking with “great certainty” based on information relayed to him by the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Office. He went as far as to tell the community that people who insist on linking fires to homelessness should “just shut up.” According to Chang, the land where the fire started is better described as an “off-the-grid neighborhood,” home to people living in RVs and mobile homes who may lack access to running water and electricity. He called it a case of rural poverty rather than homelessness.

That description immediately clashed with what Dahlgren reported and what locals like Siebert had long described. Where one side sees a makeshift community of squatters with little regard for the safety of surrounding residents, the other prefers to see a marginalized rural population struggling in unconventional housing. The difference in terminology may sound semantic, but the stakes are enormous. If a fire is traced to a homeless encampment, it strengthens the case for tougher enforcement against long-term camping on public land. If it is officially labeled rural poverty or an “off-the-grid neighborhood,” then the political implications shift entirely.

Even the Sheriff’s Office did not fully back Chang’s certainty. When reached for comment by the Bend Bulletin, a sergeant declined to confirm Chang’s statement and referred questions back to the Oregon State Fire Marshal’s Office. Officials from the Oregon Department of Forestry confirmed only that the fire started on private land within Jefferson County, leaving the investigation open. Derek Gasperini, a spokesperson for the department, emphasized that determining the cause could take weeks or even years, and that for now the priority was protecting lives and property.

The political back-and-forth did little to quiet speculation. Dahlgren’s posts from the fire line, showing ash raining down and juniper trees still smoking, continued to spread online, fueling claims that officials were hiding uncomfortable truths. His critics countered by pointing to his checkered past, including a jail sentence earlier this year after pleading guilty to misconduct while working for the city of Gresham. For supporters, however, his past matters less than the fact that he is documenting what Oregonians see with their own eyes.

It is not as though the idea of encampments starting fires is far-fetched. In 2024, a human-caused fire tied to a homeless camp scorched 80 acres on the northern edge of Bend. That blaze prompted a wave of closures and restrictions on camping in nearby areas. In La Pine, multiple fires have been traced to unauthorized camps, leading to a crackdown that remains a centerpiece of local wildfire prevention policy. Dahlgren and others argue that ignoring this history in the name of political correctness is reckless.

The Flat Fire has now become a flashpoint in a larger struggle over how Oregon tells the story of its disasters. Climate change is often cited as the main driver of wildfire risk, and no one disputes that hotter, drier summers play a role. But residents like Siebert, amplified by journalists like Dahlgren, argue that human negligence is every bit as pressing a threat. When the political class refuses to acknowledge this, they say, it only increases the odds of tragedy repeating itself.

The debate is not likely to end soon. The official investigation may take months or years, during which time speculation will continue to run wild. Meanwhile, thousands of acres of forest are gone, families have lost their homes, and those living closest to the fire line are left with little patience for abstract political arguments. To them, whether the cause is labeled homelessness, rural poverty, or an off-the-grid neighborhood matters less than the fact that Oregon’s tolerance for unregulated habitation in fire-prone lands is putting lives at risk.

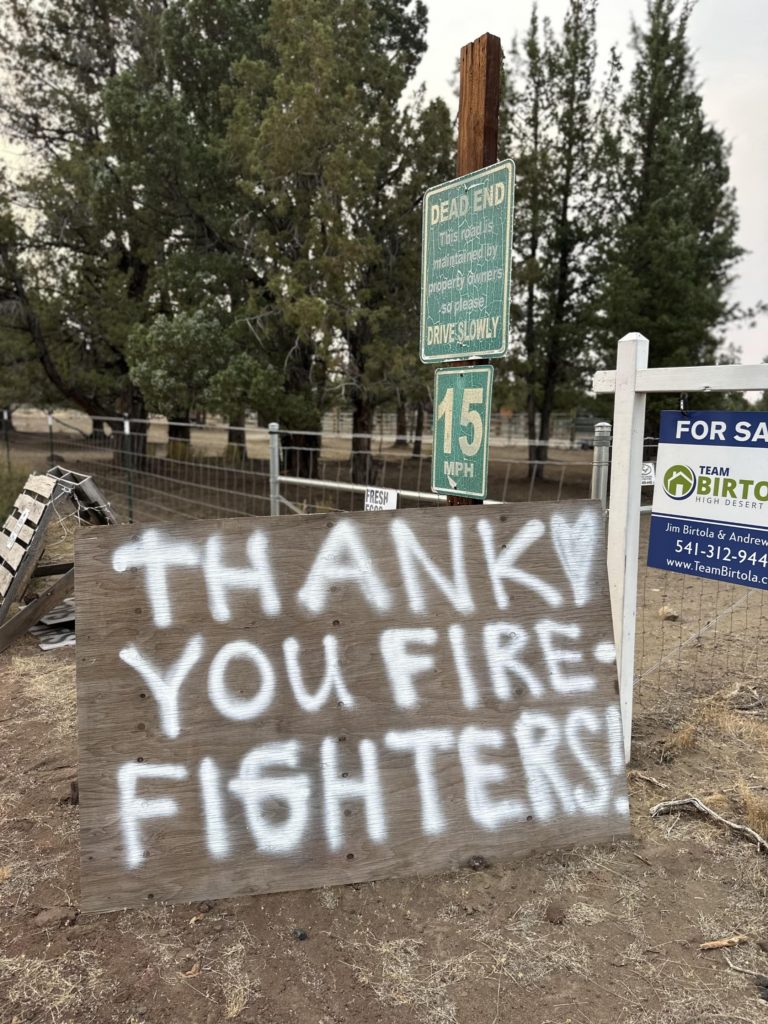

The Flat Fire has already forced the community of Sisters to the brink. At one point winds drove flames within two miles of the town. Only the combined efforts of hundreds of firefighters and favorable shifts in weather prevented a much greater catastrophe. For many, the message is clear. Unless Oregon confronts the issue of human-caused fire sources with honesty, the pattern will continue.

Dahlgren’s reporting has once again placed him at the center of controversy. His work is accused of being sensationalist, but it is also undeniable that he has brought public attention to the conditions on the ground that others would prefer to avoid. Combined with the cautious and sometimes contradictory messaging of state officials, it leaves Oregonians skeptical. If the truth is as simple as officials claim, why are their statements inconsistent and why does it take so long to confirm what really happened?

The Flat Fire is a tragedy, but it is also a warning. While investigators may eventually release a report assigning an official cause, the larger questions about accountability and prevention will remain. Oregon cannot afford to let political spin replace truth when entire towns sit in the path of the next blaze. Until those in power are willing to confront the risks of encampments, squatter settlements, and rural poverty with equal seriousness to climate change, the public will continue to doubt, and the forests will continue to burn.

If you want to help support the kind of independent, on-the-ground reporting Kevin Dahlgren is doing, you can subscribe to his Substack. He writes regularly about Oregon’s most pressing issues, often going places traditional outlets won’t, and your subscription helps him keep digging into stories like the Flat Fire. You can find his work here: truthonthestreets.substack.com.